“Cured Alright”: Freedom, Humanity and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony

Paper by Sanni Fronstenson. Viewed on DVD.

Stanley Kubrick remains one of the few directors in film history who embraced the horrors of humanity as an inseparable component of its beauty—which is perhaps why some of his films still stand among the most controversial classics of all time. Though Kubrick began his involvement with media as a staff photographer for Look magazine at age seventeen, his exposure to films from the Museum of Modern Art quickly swung his interest toward the silver screen. He completed several pet projects before making Killers Kiss in 1955, which earned him his first critical support as a director. In 1962 he released the controversial Lolita, which paved the way for a decade of harrowing classics, including Dr Strangelove (1964), 2001 (1968), and A Clockwork Orange (1971). The latter of these films is based on the novel of the same name, published by Anthony Burgess, who wrote it after his own wife was assaulted and raped by American soldiers stationed in London. The work serves as his emotional exploration of the traumatic event, a reflection upon the nature of human morality and its reliance upon freedom of choice—and Kubrick’s adaptation is faithful to these thematic concerns. McDougal’s discussion of the director’s biography notes that Clockwork remains the most controversial of Kubrick’s works, even to this day, for its bombardment of unapologetically visceral images—of ultra-violence, graphic sexuality and sexual abuse (2003). The work is a narrative of dystopian science fiction that explores a sexually and emotionally dissociated future London, focusing on a violent and immoral protagonist, Alex, who exemplifies this dissociation to an extreme degree. At the same time, the film also employs the works of several classical musicians throughout, primarily those of Ludwig Van Beethoven, to parallel the sex and violence displayed onscreen. The film uses the relationship between Alex and Beethoven as a primary device of its meditation upon the nature of human freedom. That is, these contrasting figures are used to illustrate that the human freedom we so cherish is really a double edged sword—it is a human choice, which allows the human evils in Alex to exist just as readily as it allows for the existence of those human splendors in Beethoven’s symphonies. But again, Kubrick embraces both ends of this spectrum equally, as equally vital components of human existence. His use of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony throughout the film as an accompaniment to cruelty and aggression, particularly in the Ludovico treatment scene, expresses the extraordinary flexibility which exists singularly in free will—and further, combined with several other cinematographic techniques from the scene, implies that removing this choice from Alex, even if it is the choice to be malevolent, destroys free will itself and therefore the very fabric of his humanity.

Stanley Kubrick remains one of the few directors in film history who embraced the horrors of humanity as an inseparable component of its beauty—which is perhaps why some of his films still stand among the most controversial classics of all time. Though Kubrick began his involvement with media as a staff photographer for Look magazine at age seventeen, his exposure to films from the Museum of Modern Art quickly swung his interest toward the silver screen. He completed several pet projects before making Killers Kiss in 1955, which earned him his first critical support as a director. In 1962 he released the controversial Lolita, which paved the way for a decade of harrowing classics, including Dr Strangelove (1964), 2001 (1968), and A Clockwork Orange (1971). The latter of these films is based on the novel of the same name, published by Anthony Burgess, who wrote it after his own wife was assaulted and raped by American soldiers stationed in London. The work serves as his emotional exploration of the traumatic event, a reflection upon the nature of human morality and its reliance upon freedom of choice—and Kubrick’s adaptation is faithful to these thematic concerns. McDougal’s discussion of the director’s biography notes that Clockwork remains the most controversial of Kubrick’s works, even to this day, for its bombardment of unapologetically visceral images—of ultra-violence, graphic sexuality and sexual abuse (2003). The work is a narrative of dystopian science fiction that explores a sexually and emotionally dissociated future London, focusing on a violent and immoral protagonist, Alex, who exemplifies this dissociation to an extreme degree. At the same time, the film also employs the works of several classical musicians throughout, primarily those of Ludwig Van Beethoven, to parallel the sex and violence displayed onscreen. The film uses the relationship between Alex and Beethoven as a primary device of its meditation upon the nature of human freedom. That is, these contrasting figures are used to illustrate that the human freedom we so cherish is really a double edged sword—it is a human choice, which allows the human evils in Alex to exist just as readily as it allows for the existence of those human splendors in Beethoven’s symphonies. But again, Kubrick embraces both ends of this spectrum equally, as equally vital components of human existence. His use of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony throughout the film as an accompaniment to cruelty and aggression, particularly in the Ludovico treatment scene, expresses the extraordinary flexibility which exists singularly in free will—and further, combined with several other cinematographic techniques from the scene, implies that removing this choice from Alex, even if it is the choice to be malevolent, destroys free will itself and therefore the very fabric of his humanity.

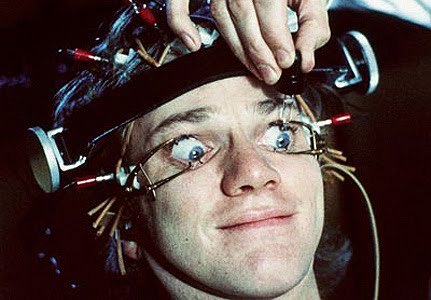

Adolf Hitler marches into the frame in a smash cut that begins the Ludovico-Beethoven scene as abruptly and disconcertingly as the beginning of this sentence. The Fourth Movement of Beethoven’s Ninth also begins on this note, and slowly ramps up in tempo and intensity to accompany a minute of recut footage from Triumph of the Will, the infamous Nazi propaganda film. This is followed by another smash cut to Alex, who sits in the Ludovico restraints and realizes which song they are playing. He screams and protests that it’s a sin to abuse Beethoven’s music, and that it isn’t fair that they’re destroying it for him. They tell him he must bear it as he writhes in torment, the score ending upon this note.

The score used for this scene is central to several of the emotional effects it produces. It defines the whole first series of images from Triumph of the Will, given that the cheery and melodically aggressive Movement is the only sound employed at all. Many brief shots of the Nazi military forces are shown in rapid succession, in direct sync to the symphony. Ranks upon ranks of Nazi soldiers march forward in unison bearing Nazi flags; military men play trumpets down a line; a conductor among a line of other military musicians thrusts a baton in unison with a high point of the music; paratroopers file neatly out of airplanes; a tank rolls through a vast field; four Nazis stand in a line as two of them beat down a door; and, finally, a statue of joyous children stands before a burning building as the lyrics begin. The use of the symphony undermines the meaning in both the propaganda footage and, more importantly, of the symphony itself. In combination with the editing work of quick cuts and the psychologically pleasing mise-en-scene elements of geometric repetitions (found in the human machinery of war), the musical synching gives the footage a meaning completely dissociated from its true social implications—it makes it cheery, artistic, almost preferable. By inversion, it equally dissociates Beethoven’s work from its culturally elevated positioning as high art, instead associating it to war, hatred and holocaust. The footage is punctuated by more somber images than the rest, and this emotional darkness produces a stark contrast to the beauty of the musical score, which seems to point to a troubling conclusion about free will: that it allowed both of these movements to occur.

The smash cut that brings us to Alex produces another juxtaposition: one between the freedom of choice (in the interpretive ambiguity of the Ninth) and the subjection to slavery, in the mise-en-scene of Alex held in a brutal restraint system. His realization of the score is met with an extreme close up of his contorting eye as he screams in agony. The score intensifies on this note, viscerally connecting the action of the symphony to the violent torment inflicted upon Alex. The whole scene is in fact framed to amplify not only the sense of Alex’s torment, but of his powerlessness and subversion to mechanization by the wills of the clinicians. These clinicians are themselves framed as robotic gods, surrounded by flickering electronic equipment and encircled by the glow of intense projection lamp backlighting. When Brodsky and Brannon speak, their sterile and subdued voices boom and echo through the intercom, whereas Alex’s screaming voice is strained and drowned out by the score. When Alex cries out frantically that it’s a sin, a wide shot frames him from a high angle at a medium-long distance, subordinating him to the scientists at the back of the auditorium that, because they are at the top of the frame, appear from a low angle. The extremely long distance range of the clinicians further dissociates them from his experience of pain, and every single shot in the scene (after the propaganda footage) contains a high angle subordination of Alex or a low angle empowerment of at least one of the scientists.

On a more shot-specific level, several techniques are used to express the inhuman nature of the treatments being administered. After they confirm Alex’s love for Beethoven, a medium shot from a low angle frames them offset to the left, and slightly tilted to the right, adding a surreal quality to the doctors’ dominance over the situation. Brodsky’s cold assertion that Alex’s loss of Beethoven constitutes the “punishment” element of imprisonment again reveals a harsh, clinical subversion of the beauty of art and human emotion in order to also subvert violence—which coincides with the disconcerting cinematography of the shot. When Alex yells that he’s cured, the match cut to a close up shot of his contorting face and darting eyes reveals the terror and torment he is experiencing, bringing direct focus to the reality that his “realization” is drug and torture induced, hardly making it a free choice. This sense of his “programmed” response is furthered in Alex’s next assertion, when his face contorts even more grotesquely and his eyes dart even more furiously as he tries to think of the reasons that people shouldn’t be randomly knived. The manic tone of his voice seems to express a legitimate sincerity in his sentiment, but the tight shot allows his darting, terrified eyes to betray this presumption. The scene ends with one last low angle shot of Brodsky, who dominates the frame in a close up as he tells Alex to leave the “curing” to the scientists. The close shot frames an extremely subtle smirk as he lays down his edict, which seems to reveal that the clinician is himself a sadist right on par with Alex. That is, he takes pleasure in the pain of another, and uses Ludwin Van to do so. Again, Beethoven’s work is used to invert our presuppositions about the beauty of free will by showing how easily the score—itself representing choice—can be used for evil.

The clinicians’ use of Beethoven as a torture instrument echoes the entire film’s use of music to demonstrate the thematic flexibility of human choice. In this and countless other scenes, characters use a culturally elevated work of beauty to instead cause harm. Most immediately, this use mirrors the Triumph of the Will segment at the beginning of the scene, which subverts the symphony by associating its meaning with the Nazi Party and the Holocaust. The rest of the film’s use of music is no different; scenes of violence are frequently played in slow motion and accompanied by grandiose classical scores from various composers, as in the highly stylized betrayal scene where Alex kicks his droogs into the lake. But the use of Beethoven’s Ninth is unique throughout the film—it serves as a symbol of Alex’s choice. As his agonizing reactions show, he hears the score as we hear it, revealing a diegetic use of the Ninth that corresponds with every other occurrence of the symphony throughout the film. That is, Alex always experiences the score as we experience it, and as Hanoch-Roe notes, it always moves the characters towards violent action (2002).

The first use of the symphony occurs early on when a woman sings part of the climax in the Korova Milk-bar, and Alex viciously belts Dim for blowing a raspberry at it. This Ninth-inspired movement of violence leads his droogs to betray him, and is therefore the catalyst for the major plot arc of Alex’s arrest and ‘rehabilitation.’ Alex next listens to it as he masturbates to visions of death, brutality and sacrilege. Again violence perversely defines and punctuates the nebulous art of Beethoven. The next use, the one occurring in the Ludovico scene, marks a turning point in the story arc where Beethoven becomes the vehicle of violence committed against Alex. Dr. Brodsky destroys Alex’s ability to enjoy Beethoven, which, given the musical development throughout the film, is ultimately a metaphor for the destruction of Alex’s freedom of choice. He can no longer tolerate art at the expense of curbing his violent tendencies—he loses his choice to do either good or evil, and in that he loses the human vibrancy that makes both aspects of human nature possible. In addition to this dehumanizing loss of choice, he loses the human right of self-preservation, unable to do anything but jump from his tormenter’s third story window just to avoid hearing the now-torturous sounds of Beethoven’s Ninth. This scandal of course catalyzes the media backlash that ultimately sets Alex free. The final climactic sequence of the symphony, played as a ‘treat’ for Alex, unleashes his human ability to choose once more, as visions of brutality and perversion return to him in a flood of orgasmic human passion—a passion of beauty, sex, high art and violence as one. He was cured alright.

Beethoven’s Ninth, as Hanoch-Roe argues, plays more than just a thematic role in the film—it also plays a structural one. As noted before, its highs and lows correlate to the actions on screen in sync, but further, the greater structures of the symphony’s four movements are echoed in the development of the film’s plot. The energetic First Movement relates to Alex’s debaucherous lifestyle and subsequent arrest, the lighthearted Second Movement correlates to the relatively comical prison sequence, the sluggish Third Movement parallels his difficult treatment and torment, and the extravagantly climactic Finale represents and actually punctuates his final redemption and ‘cure’ at the end of the film (2002). Kubrick forms a profound relationship between the art of his film and the art of Beethoven, in that he uses the composer’s symphony as the backbone of Clockwork’s structure, themes, and characterization.

Kubrick expresses a simple, but profoundly important reality about the nature of human culture by inverting a world-renowned masterpiece of high art into the soundtrack for human evil. He exploits the ambiguity and social recognition of the Ninth to reveal that meaning and value are choices to be made—that culture and art exist as natural outgrowths of human freedom equally to those of violence and cruelty. The utterly dehumanized depiction of the mechanically programmed Alex furthers this argument; Eliminating any part of human behavior, whether it be base brutality or high culture, sacrifices the paramount human ability to choose, and therefore the very essence of humanity itself. Kubrick embraces the full spectrum of human experience as universally necessary to the vibrancy of human life, and it is in this light that the irony of film’s closing line may be best understood: Alex was cured not when his psychotic tendencies toward violence were curbed, but rather when they were again unleashed, in all their fully human glory, for better or for worse—and forever with the dignity of freedom.

Works Cited

“A Clockwork Orange.” IMDb. IMDb.com. Web. 07 Apr. 2012.

Hanock-Roe, Galia. Beethoven’s “Ninth”: An ‘Ode to Choice’ as Presented in Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange”. 33.2 (2002): 171-79. Web.

Maestu, Nico E. “Filmstudies Online Lectures.” Lecture. Filmstudiesonline. Web.

McDougal, Stuart Y. Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Barsam, Richard. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 3rd Edition. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010.

About this entry

You’re currently reading ““Cured Alright”: Freedom, Humanity and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 05.10.12 / 11am

- Category:

- Academic Papers, DVD, Films

2 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]