Caesar Must Die (Paolo Taviani, Vittorio Taviani, 2012): Italy

Reviewed by Laura Wyatt. Viewed at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival, 2013.

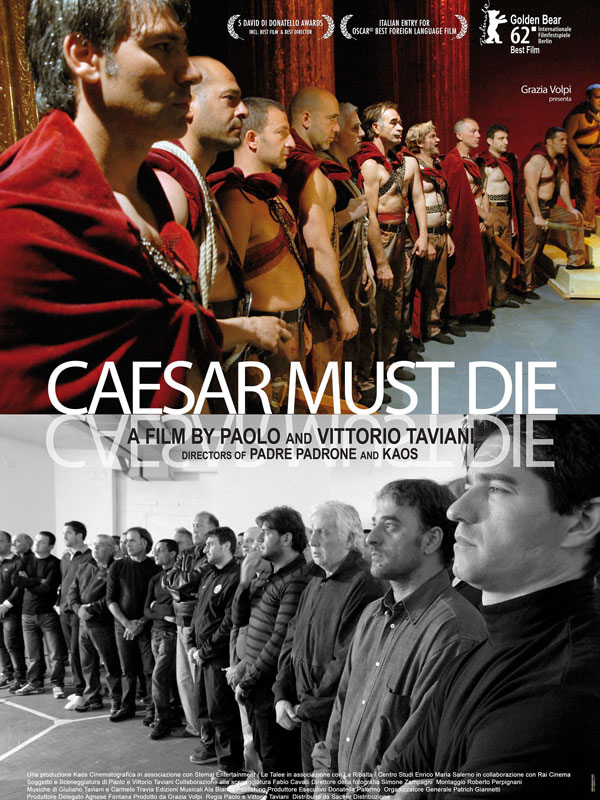

When Caesar Must Die opens, you don’t know where you are. You are watching the end of a play. Everything looks like it should, actors on stage, audience engrossed in the performance and applause at the end. What you don’t realize until later is that all of this is taking place in a maximum-security prison and the actors are the inmates.

We learn this as the guards are unceremoniously taking each prisoner back and locking them in their cells after the show is over. As the heavy black doors slam behind them, the film moves from color to black and white and we are transported back to six months earlier.

We learn that each year the jail puts on a play using the inmates as actors. The prisoners live for this once-a-year production and are all quite accomplished actors. The play being tackled this time is William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. We see that it all begins with the auditions, which are cleverly shown from a stationary camera and it’s the actors that come to it. They are all given the same scene to repeat and we get to see it from a casting director’s point of view. We see the progress of the play from a “table reading” to the finished performance on stage and the journey is fascinating.

As the cast takes shape we are introduced to the players and are shown (in writing) their crime and sentence. Some are in for drug trafficking others for murder. These are hardened criminals and look the part. The black and white imagery adds to the gritty look of the men, unshaven and unclean and in isolation for most of their lives.

The vast majority of this movie uses direct dialog from Shakespeare’s play, in fact he receives a writers credit. It is sometimes hard to tell when the players are using their own words or that from the script. Their lives often parallel the plot of Julius Caesar.

There is a wonderful scene showing two actors in their individual cells rehearsing by themselves but out loud. The way it is edited makes you think they are in the same room doing a reading together and it brings back the sad truth that they are locked away. They don’t have much else to do but rehearse and since they are allowed access to different areas of the jail, it must feel like freedom to them.

There is clever use of music as well which really only comes into play towards the end. As the play becomes more tension-filled, so does the music and it helps move the scenes along.

As we are brought back to the present, we see the men talking just before they are about to go on stage for their opening. They are still speaking dialog from the script but it portends what is about to happen. They are plotting the death of Caesar and say they don’t know how the night will end, just as they don’t know how their night as actors will end. The film reverts back to color and we are right back on stage where the film started, near the end of the play. We are treated to a bit more of the plays ending scenes and shown the empty seats of the audience.

Our last image is a sad one as a prisoner, back in his cell, says to himself, “since I got to know art, my cell has become a prison”. At least he has next year’s performance to look forward to.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Caesar Must Die (Paolo Taviani, Vittorio Taviani, 2012): Italy,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 01.31.13 / 10am

- Category:

- Films, Santa Barbara Film Festival 2013

1 Comment

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]