From shipping Chevrolet to shipping Cannons

Paper by Sofia Nagel.

Frank Capra’s Prelude to War (1943) could not exist without Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935). The propaganda films share many of the same editing techniques, frames, modes and visuals. The American and German government capitalized on the film industry to propagandize the public. Triumph of the Will and Prelude to War are propaganda in equal measure though of opposing countries. World War II brought out a cold, calculating Hollywood that aggressively and frankly manipulated viewers’ emotions. Films had a new a mission to convey the messages of their government. Frank Capra and Leni Riefenstahl were commissioned by their government for this very reason. Through propaganda in Hollywood, entertainment was used to garner trust, knowledge, and patriotism.

Frank Capra’s Prelude to War (1943) could not exist without Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935). The propaganda films share many of the same editing techniques, frames, modes and visuals. The American and German government capitalized on the film industry to propagandize the public. Triumph of the Will and Prelude to War are propaganda in equal measure though of opposing countries. World War II brought out a cold, calculating Hollywood that aggressively and frankly manipulated viewers’ emotions. Films had a new a mission to convey the messages of their government. Frank Capra and Leni Riefenstahl were commissioned by their government for this very reason. Through propaganda in Hollywood, entertainment was used to garner trust, knowledge, and patriotism.

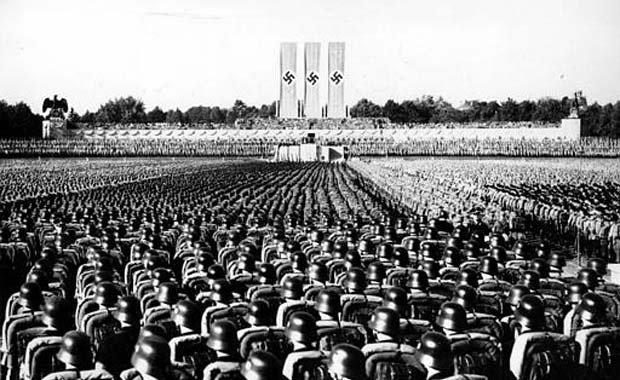

The opening of Triumph of the Will begins with the following statement: “September 4, 1934. 20 years after the outbreak of World War I, 16 years after German woe and sorrow began, 19 months after the beginning of Germany’s rebirth, Adolf Hitler flew again to Nuremberg to review the columns of his faithful admirer.” Horst-Wessel-Lied, the national anthem of the Nazi party coos in the background. With a vantage point from a plane, Adolf Hitler seems to be flying the plane and in complete control. This gives him a God-like representation as the plane lands and Hitler leaves the plane – seemingly cascading from the Heavens. There is an ethereal, powerful quality to Hitler’s introduction. The documentary follows Hitler’s arrival in Nuremberg, records his presence at rallies and speeches, and concludes with his final address. The structure of Triumph of the Will is straight-forward, linear, and easy to comprehend. Leni Riefenstahl (with the assistance of 18+ cameramen) brilliantly and calculatedly arranges frames, shots, and the cinematography. The audience never directly looks at Adolf Hitler; we are only exposed to his profile or him looking onward at his people, smiling and waving at children and pretty young women. This tactic gives Hitler celebrity and presents him as unattainable – we are given just enough of Hitler to want more. Viewers find themselves craning their necks to get a better look at Hitler – as his followers did.

Riefenstahl makes the audience feel as though they are there. There are many aerial views of Hitler, reiterating his God-like power. Movement was incredibly important to Riefenstahl, “There must be movement. Controlled movement of successive highlight and retreat, in both the architecture of the things films and in that of the film,” (55, Document or Artifice?) Triumph of the Will was like Hitler’s debutante. Reich president Otto von Hindenburg had recently passed away, relinquishing all power to Hitler and permitting him to take the role of president. Hitler needed to present himself as the worthy and all-powerful leader of the German people. Adolf Hitler had previous discord with the German military; he knew that in order to grasp full power, he would need them by his side. There are many shots of smiling, joyous military figures at the rally. Every image that we see in Triumph of the Will has an agenda. Even the circumstances were orchestrated solely for the film, “the Convention itself had also been staged to produce Triumph of the Will, for the purpose of resurrecting the ecstasy of the people through it,” (51, Document or Artifice?).

Frank Capra’s Prelude to War was commissioned by the Office of War Information and George C. Marshall, with the intention to show America and American soldiers, why the United States was involved in the war and why the U.S. deserves your support and your participation. Capra uses newsreels footage, captured footage, re-enactments, animation and (some) factual information to promote the cause of the United States. The film opens with a tracking shot of American Soldiers. Decorated, defiant, and debonair, audiences are proud of their soldiers. With a God-like voiceover, we are reminded that we are a peaceful country, one that does not involve itself in unnecessary conflict, like other countries (shot to clips of discord in Britain, France, China, Poland, Holland, and Greece). Despite our peaceful intentions, aggressive countries that envy our great country will attack (shot to the attack on Pearl Harbor). This tactic makes one reflect on the tragedy and devastation caused by the attack on Pearl Harbor. It feels fresh in the viewers’ mind again, we have entered a mindset that seeks retaliation. The audience is then told the statement, “this is a fight between a free world and a slave one.” There is an emphasis on racism. During this time, tensions were high in the United States with Japanese and German people. Capra fully capitalizes on that. We hear an excerpt from the Declaration of Independence, “Give me liberty or give me death.” The narrator then asks us, “But what about this other word?” There is an immediate shot to Japan, Italy, and Germany. Capra’s goal, according to War without Mercy, was to “let the enemy prove to our soldiers the enormity of his cause – and the justness of ours,” (16).

Frank Capra compiled enemy newsreel, films, and speeches to display to the audience why we were fighting and what we were fighting for. Capra even used clips directly from Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. Rather than focusing on the United States and the greatness of the country, like Triumph of the Will does, Capra came from a different angle and that was to compare our country to ones that committed such atrocities. The manipulation of viewers’ emotions is frank and unabashed. Why We Fight aims to establish the strength and power of the United States and to persuade viewers’ that war is sometimes necessary to protect our great country – but rarely, is war our fault. Why We Fight uses a variety of tools to make that point clear. The film uses decades-old archival Axis powers footage as one tool and as another powerful tool, animation. The animation was produced by Disney studios. It appeals to children and is easy to comprehend and entertaining. The animated maps that are presented to the audience portray Axis-occupied territory in black. It is these subtle and not so subtle propaganda techniques that sway the audience into the direction that the government wants. The film is vibrant, visually-striking, and emotional. It is equipped with all of the tools necessary to inform and persuade.

“Triumph of the Will fired no gun, dropped no bombs. But as a psychological weapon aimed at destroying the will to resist, it was just as lethal.” (328, The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography). Frank Capra’s Prelude to War and Why We Fight could not of come into fruition without the assistance of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will and the brilliant and innovative techniques that she introduced. Frank Capra created an antithesis of Triumph of the Will. His films, at times, feel like a reaction to hers. The filmmaker used her work as a base to build on. For example, Capra includes many actual clips from Triumph of the Will to assert his claims and to create the light/dark, good versus bad theme that he uses in Prelude to War and the Why We Fight series. In War Without Mercy by John Dower, he focuses on the emphasis of good and evil, “In Prelude to War, the “two worlds” were illustrated as literally as can be imagined by drawings of two globes, one black and the other white,” (17). Frank Capra capitalized on the racial tensions in the United Sates with Japanese and German people. In his political films, Capra invites the audience to compare the United States to other much older countries. By showing speeches and other footage of enemy countries, he is breeding more hate and reinforcing where the United States as a country should stand. The message is much more overt than in Triumph of the Will, which focuses solely on Hitler’s rise to power and Nazi Germany. While Capra uses rhetoric in his film that makes the point very black and white: “freedom versus slavery,” “good against evil,” even “the Allied “way of life” rather than the Axis “way of death.” Why We Fight and Prelude to War use Triumph of the Will as a jumping off point. Capra takes the evil that he saw in Triumph of the Will and exposes it, in a sense, by responding to it. In War without Mercy, Capra is quoted as saying, “Let our boys hear the Nazis and Japs shout their own claims of master-race crud and our fighting men will know why they are in uniform.” However, Frank Capra did not let the footage alone do all the work. Powerful narration and use of sound emphasize these comparisons. Why We Fight does not have the same intentions as Triumph of the Will whose goal is to promote its’ leader while Why We Fight explains why we are involved in the war. The films share many similarities. Both Frank Capra and Leni Riefenstahl capitalize on footage of children to evoke ardent feelings in their audiences. Editing and sound are also paramount for both Triumph of the Will and Why We Fight. Capra recognized the prowess and political influence behind Riefenstahl’s filming techniques. The films follow a performative mode by using tools such as archival footage, footage of conferences and demonstrations, speeches, animation, and illustrations. Both films have a strong rhetorical argument that aims to persuade and convince the audience. The directors use many propaganda techniques to achieve this; such as angles, use of color (in Capra’s case), illustrations, and sound.

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” -George Orwell. Frank Capra and Leni Riefenstahl both engage in this practice. In Triumph of the Will, Adolf Hitler’s carefully-crafted image is displayed as he takes full control of Germany. The film introduces him and what he stands for; it represents his political and social power; it tracks the type of people that follow and depend on Adolf Hitler. There is footage of the military to show that Hitler has no conflict with them and is ready to prevail and conquer. Triumph of the Will is like an exaggerated campaign commercial for a politician. Hitler is presenting himself as he wants to be seen by Germany. The film does not address any controversies but rather what he would like people to know and to believe. In this way, it is denying history and showcasing a leader that does not, in reality, exist. Yet, the smiling faces of babes, of handsome soldiers, and of beautiful women waving, says something to the contrary. Frank Capra’s Prelude to War and Why We Fight explain the history of the United States, as the United States, would like the audience to see it. In this regard, it is not much different from Triumph of the Will. The audience listens as the narrator quotes the Constitution and watches as liberty bells swing past. It is aggressive and blatant propaganda. Then there is frank blaming. It feels like an army recruitment video that states its’ country can do no wrong, or at least the country’s shortcomings pale in comparison to that of more extreme countries, like Germany, Japan, or Russia. The film essentially says, “Look how lucky you are and look how these barbarians live, you don’t want to be like them, do you? So let’s fight!” However, war is never just black and white, the central colors that Capra uses to express his point. It feels like propaganda for a child. The colors are vivid, the narrator practically tells the audience how to feel, the use of blacked-out maps and cartoons comes across not as sophisticated and subtle, like Triumph of the Will, but in your face and agenda-ridden. Despite the fact that Triumph of the Will has a much bigger agenda, it is laced with careful propaganda. Instead of feeling like Alex in A Clockwork Orange with our eyes glued open, Triumph of the Will gives you the impression that you came to these beliefs and conclusions all on your own. It does not feel as much like propaganda as Capra’s films. However, this is not the case as it was just done differently and more covertly. Propaganda is one of the most useful tools in war. It can be used to make men and countries go to war. It is powerful and dangerous and by using it in film, it becomes even more powerful, particularly when movies were the primary source of entertainment and meant to be a form of escape during World War II. One becomes unable to differentiate between entertainment and brainwashing. Triumph of the Will is a beautiful and visually-striking movie and like Frank Capra said, it drops no bombs or violence. It is instead something more powerful that any weapon: that of image and of words. An image of a smiling child waving at Hitler can change the perspective one has of the man (or at least could have then). It is with careful and deliberate consideration that the directors choose the images that they did. One has to also question everything that they see and that they hear. There is propaganda laced in nearly all of our entertainment sources and it’s up to us to find our truth. Triumph of the Will created a new breed of films and received many awards and many imitations. Without the creation of it, many films, including Frank Capra’s, may never exist.

Works Cited

Capra, Frank. The Name above the Title: An autobiography. New York: Macmillan, 1971. Print.

Dower, John W. War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York: Pantheon, 1986. Print.

Hinton, David B. “”Triumph of the Will”: Document or Artifice?” Cinema Journal 15.1 (1975): 48-57. JSTOR. Web. 15 Apr. 2015.

Springer, Claudia. “Military Propaganda: Defense Department Films from World War II and Vietnam.” Cultural Critique No. 3.American Representations of Vietnam (1986): 151-67. JSTOR. Web. 15 Apr. 2015.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “From shipping Chevrolet to shipping Cannons,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 07.18.15 / 9am

- Category:

- Academic Papers, DVD, Films

2 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?]