Documentaries: Capturing the Reality of Rural Life

Paper by Becca Knowlton.

Documentaries strive to capture the reality of the moment. Many succeed and shed light on the average person by exposing their everyday simplistic way of life. Over time these expository films have progressed in their way of observance from the silent surveillance of Robert Flaherty in the 1920’s to actual probing interviews by Michael Moore in recent years.

Documentaries strive to capture the reality of the moment. Many succeed and shed light on the average person by exposing their everyday simplistic way of life. Over time these expository films have progressed in their way of observance from the silent surveillance of Robert Flaherty in the 1920’s to actual probing interviews by Michael Moore in recent years.

Filmmakers Dziga Vertov, Barbara Kopple, and Christopher Guest have each made movies that observe basic human daily existence. Man with a Movie Camera (1929) is a silent feature which has no plot or actors and shows average Russian life through the impartial perspective of the director. Based on actual events Harlan Country, USA (1976) follows citizens of Eastern Kentucky around as they fight against the big coal corporation which is ignoring the workers rights. Waiting for Guffman (1996) takes the mockumentary approach and humorously focuses also on a small town which is preparing to put on a local theatrical production.

These three films give viewers key insight into other walks of life which “enables us to live our lives a little more fully and intelligently” (Ellis & McLane 2). It is the director’s intent to encourage social change through their observance and representation of stereotypical ‘actual’ life. These movies are “committed to the richness and ambiguity of life as it really is… (they) exist to scrutinize the organization of human life and to promote individual, humane values” (Rabiger 4).

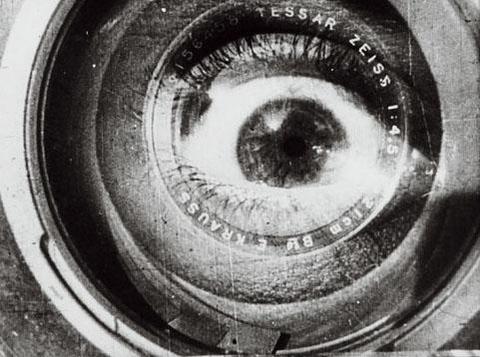

One of the forefathers for this style of film is Soviet born Dziga Vertov. He became interested in film when he noticed a connection between “the filming process and human thought” (Ellis & McLane 28). However he believed that the camera was more objective. “He clearly saw it as some kind of innocent machine that could record without bias…the world as it really was. The camera lens was a machine that could be perfected bit by bit, to seize the world in its entirety and organize visual chaos into a coherent, objective set of pictures” (Dawson).

In 1929 he released Man with a Movie Camera which follows him around the city as he records different aspects of daily Russian life. It has no plot, characters, and sound except an accompanying musical soundtrack which is nondiegetic. This film is infamous for its various new filming techniques such as the use of odd angles and fast cutting. According to authors Ellis and McLane it is one of the densest, most complex and experimental films ever created (34) for its time. The entire film consists of “an impressionistic montage of Moscow life from dawn till dusk” (34). Scenes juxtapose between Vertov’s camerawork and then shots showing him actually filming what he is taking place. Legendary British filmmaker John Grierson concludes that it is “in consequence not a film at all: it is a snapshot album” (Dawson).

Its opening scene begins with the start of a new day. Images show life almost frozen in time. Streets are empty, local parks are bare, and machinery is unused while people lay continuous in slumber. Babies are seen sleeping while wrapped tightly in clean blankets in a sterile hospital as opposed to the vagabond sleeping in rags in the dirty city streets. A single car pulls up to a house as the silhouette of a man with a camera climbs in. The city begins to awake as he films. Men go to work, women get dressed and the children play.

The tempo becomes rigorous and repetitive. Perhaps nothing happens which would be considered monumental to the viewer, but in the lives of the people featured this is all they know. Shots are shown of people brushing their teeth, riding in carriages, shopping at the market, and even applying for a marriage license. It is a time capsule of history as it allows anyone to go back and physically visualize what life was like in early 20th century Russia. It is unbiased as it focuses on all walks of life; rich and poor, young and old through the clever use of montage editing.

Cinematically Vertov puts careful consideration into showing the different elements and aspects from every type of person in the same day. He often includes shots of the camera to perhaps remind the audience they are indeed watching only a film. Many scenes contrast with each other such as the young couple happily getting married and the old woman mourning on her knees in an abandoned graveyard. A rich woman gets her hair washed at a salon while another woman robotically performs the grueling task of cleaning laundry. With each juxtaposing image we learn more about basic human life as we compare the thousands of images flashing before our eyes.

Many years later halfway across the world another director was able to capture the authenticity of the moment. Barbara Kopple is not only a pioneer for women directors in film, but a key activist for exposing real life stories which would otherwise go unheard of. The entertainment business has typically been male driven with the exceptional few women who stand out as costume designers, screenwriters, and actresses. Why is this? Many critics believe that male written drama containing heroes and violence will make more money than that of a sentimental chick flick. As Linda Serger observes “Character, behavior, emotions, and relationships are emphasized over and over again by women filmmakers. Some say this stereotypical. But gender research continues to indicate there is a difference. Women’s experiences tell them that they are more emotional and relational than men” (Serger 116). Simply put author Linda Serger states that “women’s films are personal. Subjective” (117).

A telling example of this is Kopple’s success in Harlan County, USA. It focuses on the clashes between the workers and owners of the Duke Power Company in urban Kentucky. The director and camera crew follow around the participating boycotters who refuse to return to work until their rights are reviewed and accepted by the officials. “Kopple’s camera focuses on the desperate plight of people still living in shacks with no indoor plumbing and working dangerous jobs with little security and few safety rules” (NYT Review).

It takes place in a small rural town deep in the woods which prides itself on its traditions and values. The people are in no way glamorized or idolized. In their old worn clothes they speak into the camera sometimes with toothless gums about how they deserve the respect from the slightly more successful businessmen. No attention is focused on their physical features, but strictly to their justified emotions. The atmosphere is raw and real as it shows contending humans struggling to see eye to eye over the basic necessities of life. Looking back on the experience Kopple says “I learned what life and death was all about. I learned what it meant to give up everything for what you believed in” (DocTalk).

The film begins with a montage underground showing the miners daily tasks. This lets the audience immediately know just how difficult the situation is and shows why the coal miners are asking for a better way of life. A folksy bluegrass song plays in the background which goes hand in hand with the content on the screen. Different townsfolk are interviewed outside their homes and each share the same story about the passion the people feel for justice. Scenes juxtapose between local town hall meetings and press conferences involving the company’s owners. Through the clashing scenes of showing the different opposing sides the viewer begins to understand the situation. The representatives for Duke Power claim they have offered many contract upgrades, the ‘gun thugs’ hired by the company proclaim the danger behind organized unions, the miners and their supporters simply want better pay, safer working conditions and equal rights and the police officers simply want to keep entire town in order.

As the film progresses over the next few years the tension has risen to an unbelievable level. The striker’s supporters have grown in numbers and they picket outside the factory daily for extended hours. A popular potentially elected union representative and his family are mysteriously killed in their home. The ‘gun thugs’ are now threatening and acting out with extremely violent threats even against the women. The climax of the documentary appears to be a scuffle at night between the ‘scabs’ and strikers in which a young man is shot in the head with a gun and killed. Finally there seems to be a mutual agreement between the sides and eventually a compromise is reached after years of unbelievable disagreement and struggle though nothing has dramatically improved.

The images of this rural way of life are very haunting. It humbles the viewer to see how difficult some others have it, yet they still get by. The people shown in the film represent the backbone of America. They are hard working blue collar workers who do not have much to call their own, but it is all they have. No actor could ever portray the raw emotion brought to the screen. This film focuses not only on the progression of American justice for all, but on the basic rights that every human should be entitled to. From an impartial third party observer we have a ‘fly on the wall’ perspective as we witness how the working middle class Americans struggle between justice and progress.

As time and society progressed a more humorous approach was taken to represent the average person in their every day life. Director Christopher Guest is known for his ‘mockumentaries’ which comically document regular people in normal situations. Famously it is known that he dislikes the use of the word because he feels that he is not actually mocking anything (Rose). He plays into the stereotypes and focuses on average looking people who have intense passion for things otherwise overlooked at by the general public. In referring to these individuals Guest says, “There is a big world out there that is hidden in many cases and I think it is very interesting to go into those…” (Rose).

Waiting For Guffman follows the lives of citizens from Blaine, Missouri as they prepare to put on a community theatre production for a potential big wig New York City producer. The hand held camera follows around quirky director Corky St. Clair through the process of holding auditions, rehearsals with the cast and the infamous opening night. It is meant to seem completely realistic as it genuinely focuses on real people going about their day although the story is actually fictional and the dialogue is all improv. The characters are “self-serious… (and) unveiled in long addresses to the camera; they all seemed to have strange talents and, in the end, the oddballs would assemble together for a climactic…event in which they would transcend their idiocy and somehow emerge triumphant” (Curtis). The cast of regular Joe’s include an eccentric married couple, a nerdy dentist, a retired taxidermist, and a bubble blowing teenager who works at Diary Queen.

Of course drama unfolds as problems come up with casting, finances, and ego to name a few. The film has a slow start in which the world of the characters is introduced, but picks up as the individuals stories get intertwined as they come together for a common goal. In hindsight no real ‘climax’ ever takes place as the film rolls along at an uninterrupted pace as life sometimes has the tendency to do. The story begins and ends as it started. There is no life lesson learned and nothing momentous happens in which changes the lives of the characters/real people forever. In the end the producer never actually shows up, so all the hype was in vain. In the world of the story/ ‘reality’ life simply continues on its way as everyone goes on about their normal day. Libby Mae returns to her fast food job and Corky moves back to New York and opens a novelty store. The documentary was just a snippet out of every day existence in the world of these fictional characters.

One of the biggest differences between the previously mentioned documentaries is that Guffman seems to focus and depend on the interviews of the townspeople to carry the storyline while Man with a Movie Camera and Harlan County have enough drama visually that no narration to explain what is happening. Yet a common thread these three films share is that in the end nothing has really changed. The monotony of life still continues for the people in Russia, the workers still complain about their jobs in Kentucky and the producer never shows up to critic the play in Missouri. No matter what country, year or problem life proceeds to continue on.

The films were released in completely different decades through out history and yet seem to follow each other linearly by showing the repetition of human existence, the progression of society and even advances in the film business. Man with a Movie Camera, Harlan County, USA and Waiting For Guffman all share the common purpose of the desire to expose the reality of everyday life as opposed to the written Hollywood stories which are usually unrelatable. They show the repetitiveness, the spontaneous, the ugly, the beautiful, and the painful sides of life that few often see. In capturing these moments the viewer is allowed to witness and potentially understand the world from other people’s perspective which is vital as it enables us to assess the world around us through the eyes of someone else.

Works Cited

“A Conversation with Director Christoper Guest.” Interview by Charlie Rose. The Charlie Rose. PBS. 12 May 2003. Television.

Curtis, Bryan. “The Problem with Christoper Guest.” Slate Magazine. 26 Nov. 2006. Web. 18 Nov. 2009.

Dawson, Jonathan. “Dziga Vertov.” Issue 51, 2009 – Senses of Cinema. Web. 19 Nov. 2009.

“DOCTalk- Interview with Barbara Kopple.” DOCTalk. Documentary Channel. 24 July 2009. Television.

Eder, Richard. “Harlan County, USA (1976).” Rev. of Movie Review. The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 18 Nov. 2009.

Ellis, Jack C., and Betsy McLane. A New History of Documentary Film. New York: Continuum, 2005. Print.

Harlan County, USA. Dir. Barbara Kopple. First Run Features, 1976. DVD.

Man with a Movie Camera. Dir. Dziga Vertov. Perf. Dziga Vertov. Google Videos. 2007. Web. 18 Nov. 2009.

Rabiger, Michael. Directing the Documentary. Boston: Focal, 1987. Print.

Seger, Linda. When Women Call the Shots. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1996. Print.

Waiting For Guffman. Dir. Christopher Guest. Perf. Christopher Guest and Eugene Levy. Sony Picture Classics, 1997. DVD.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Documentaries: Capturing the Reality of Rural Life,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 12.11.09 / 10am

- Category:

- Academic Papers, Films

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]