1778 Stories of Me and My Wife (Mamoru Hoshi, 2011): Japan

Reviewed by Richard Feilden. Viewed at the Santa Barbara Film Festival 2011.

Based on the true story of Taku Mayumura, 1778 Stories of Me and My Wife is a tale both delicate and powerful, whimsical and emotionally wrenching, a delicious confection wrapped around an inevitable bitter pill. It’s also a bloated mess that needs an unflinching editor to carve it into shape. I love the film, despite its flaws, but I know that, with a little less, it could be so much more.

Based on the true story of Taku Mayumura, 1778 Stories of Me and My Wife is a tale both delicate and powerful, whimsical and emotionally wrenching, a delicious confection wrapped around an inevitable bitter pill. It’s also a bloated mess that needs an unflinching editor to carve it into shape. I love the film, despite its flaws, but I know that, with a little less, it could be so much more.

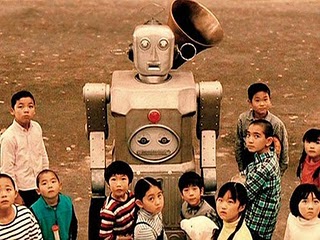

Saku (Tsuyoshi Kusanagi) is a passionate science fiction writer, who has found a little success crafting short stories for a magazine. He is blessed with a wife, Setsuko (Yuko Takeuchi), who not only supports him in his calling, but who shares his child-like enthusiasm for the weird and the wonderful. Beautiful 1950s kitsch robots fill their lives, from the tiny models which command every inch of his study, through the pages he writes, and beyond into his subconscious, his dreams. Saku and Setsuko live like children, skimming the surface of reality, but never becoming submerged in it. That makes it all the more heartbreaking when their fantasy turns nightmare. Instead of a hoped-for pregnancy, Setsuko is condemned by a diagnosis of terminal cancer. Spurred on by a doctor who extols the benefits of laughter as medicine, Saku promises himself that he will write a funny story a day – not for publication, but as a sign of love, and symbol of life, for his wife.

Saku is as innocent a character as I can remember. As the film plays out from his perspective, it’s almost impossible not to be caught up in his world, and his refusal to accept the harsh reality that stalks the story. In some of the film’s best moments, we literally see his imagination take flight. Tower blocks morph into giant mechanical monsters in his mind’s eye, and the toys in a shop window march back and forth for his pleasure. We even join him in a struggle to save old robots from terrible new ones on some far flung moon. That the director manages to make such whimsy feel completely appropriate in a film about their struggle with Setsuko’s unjust impending mortality is quite astonishing to me. It never cheapens the proceedings, never feels out of place.

In part, this is due to the performances of the two leads. As Saku, Tsuyoshi Kusanagi makes a wonderful Peter Pan figure, not fighting against the idea of growing up, but simply immune to its grip. Yuko Takeuchi, playing Setsuko, tempers her own flights of fancy with just enough of an edge of responsibility to ground their relationship and make their ability to function in the real world seem plausible. Had she fallen too close to Saku’s naiveté, the film would have been to fanciful to connect to its weightier elements. If she’d been too serious, then their relationship would have been unbelievable. Much of the film’s strength lies in her quiet supporting performance. Another part can be credited to the film’s look. The cinematography is crystal clear and the sets bereft of unnecessary clutter. When this is paired with the animated robots, thankfully more Robbie than Optimus Prime, the effect is quite simply beautiful.

It is only when the ‘1778 stories’ near the end of their inescapable countdown, that the film begins to fall apart. It is as though the film is as desperate to hold on to Setsuko as Saku himself. The final act, set around her hospital bed, drags interminably, with unnecessary repetition piled on top of unnecessary repetition. I understand the need to make the final moments drag , to highlight the rapid flight of past days taken too much for granted, but the film stretches this to the point of absurdity. When the audience begins to wish for the end, the film is in danger of undoing all that it set out to achieve.

The story goes that Michelangelo could look at a rough block of marble and see the beauty of the statue within, waiting to be revealed as the excess was trimmed away. That’s exactly how I feel about 1778 Stories of Me and My Wife. At nearly two and a half hours, the film is overlong and baggy, its potential buried beneath an overlong third act. If it is not cut down before it is released from the festival circuit, I fear it is doomed to fail. But even if you come across it uncut, I implore you to give the film a chance. Stick with it through the hard times and hold on to the best moments. They are what you’ll remember in the end.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “1778 Stories of Me and My Wife (Mamoru Hoshi, 2011): Japan,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 03.13.11 / 10pm

- Category:

- Films, Santa Barbara Film Festival 2011

1 Comment

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]