New Are Noir

Paper by Veronica Lee Rice. Viewed on DVD.

David Fincher is an auteur director most famous for films like his cult classic Fight Club (1999) and his Oscar-nominated films The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) and The Social Network (2010). His oeuvre also includes the psychological thrillers Se7en (1995), The Game (1997), and Zodiac (2007). With a background working for George Lucas’ Industrial Lights and Magic and years involved in directing television commercials and music videos for stars such as Madonna, The Rolling Stones, and Michael

David Fincher is an auteur director most famous for films like his cult classic Fight Club (1999) and his Oscar-nominated films The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) and The Social Network (2010). His oeuvre also includes the psychological thrillers Se7en (1995), The Game (1997), and Zodiac (2007). With a background working for George Lucas’ Industrial Lights and Magic and years involved in directing television commercials and music videos for stars such as Madonna, The Rolling Stones, and Michael

Jackson, David Fincher is a polished director with the means to get serious funding (Lindsay). His previous work has allowed him complete creative control over most of his films, allowing him to genuinely express his ideas. Many of his films focusing on the bad things people do to other people, which makes it is no surprise that Fincher draws inspiration from film noir. As the times change, so does the genre, and Fincher has an affinity for developing revisionist noir films. By tweaking genre conventions, he creates new sign-systems and adapts noir to modern times. David Fincher utilizes common techniques of noir, such as voiceover narration and flashbacks with the double protagonist in films like The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Fight Club, and Se7en to redefine genre specifications and sign-systems.

Even Fincher’s three-hour emotionally powerful epic, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button contains these elements of a noir film. Although the film does not closely follow most noir themes or conventions, the use of voiceover and the flashback still denote Fincher’s love for the genre. Benjamin Button is his most mature work, taking as much time and space necessary to develop a genuine story, relatable characters, and a love story for the books. Benjamin Button takes place in modern times—hours before Hurricane Katrina hits New Orleans. An old woman on her deathbed in a hospital asks her semi-estranged daughter to read her an old journal—Benjamin’s journal. As Caroline reads to Daisy, the flashback begins and Benjamin’s voice takes over the narration; he is long dead, but the words in his journal are still very much his own. Caroline reads on, and the audience learns that Benjamin is her father with her—the images on screen are of Daisy holding her new baby with Benjamin lovingly and protectively sitting leaning over them. As the narration reveals the baby’s name is Caroline, “And we named her for my mother, Caroline” the voice changes from Benjamin’s to Caroline’s, and the scene returns to the hospital. As reliable of a narrator as Benjamin is, the jarring switch from him to Caroline disrupts the ease of the story. All through the film Benjamin’s story is interrupted by moments in the hospital, creating a sense of disharmony and breaking the realism, reminding the audience that they are not witnessing life as it happens. Like a film noir, this film uses specific conventional elements—notably the voiceover and flashback, and subtle tones and themes critiquing the American Dream, but most of the similarities between the film and film noir stop there. David Fincher draws on noir for inspiration and pays homage in many ways.

Like many classic noir films, Fight Club starts at the end and flashes back to the beginning, with the narrator recounting the events past. This glimpse of the genre is one of the few defining signifiers indicating a reference to noir. Dussere points out

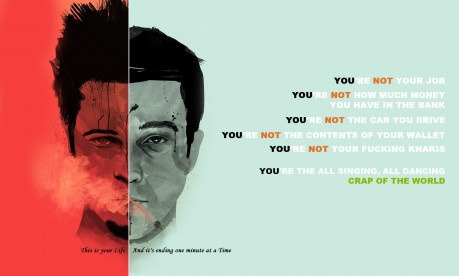

David Fincher’s 1999 Fight Club, has few of the obvious plot elements we associate with classic noir: no detective, no murder, no heist gone wrong. Rather, Fincher gives us the alienated mood, the stylized “realism,” and the skepticism about the American mainstream that we recognize as noir.

Because he depends on noir technique more than noir themes, the practice of these methods is crucial to understanding how he changes the genre. Fight Club is highly stylized, paying homage (in its own right) to the stylization of German Expressionism and noir. With quicker editing and a dirtier, dinger mise-en-scene, the film only alludes to neo-noir. While the main action of noir films takes places on the “mean streets,” the majority of the action in Fight Club takes places indoors—in gritty basements or Tyler’s dilapidated house. Still, the film oozes the dark, cynical feelings about the American Dream, embodied in noir films. But Fincher’s film does not examine itself as a film or as the recreation of a genre. Dussere also broaches the idea that “instead of taking a critical attitude toward classic film noir, [Fight Club] blends elements of noir narrative with a flashy contemporary visual style that is indebted to MTV and television commercials.” This can no doubt be attributed to Fincher’s own background in television commercials and music videos. His modern take on the aging genre complies with revisionist tendencies of stylistic complexity and intellectual appeal. Genre identities are always changing due to changing conditions, circumstances, and historical conditions. Not unlike Stanley Kubrick, Fincher redefines the genre of noir while still using one of its primary attributes: voiceover narration. The unnamed narrator (“Jack”) in Fight Club is just as unreliable as Kubrick’s 1971 A Clockwork Orange’s Alex, but in both cases, the audience has only the narrator to rely on to tell the story. With a gun in his mouth, the unnamed narrator of Fight Club (commonly referred to as “Jack”) mumbles out vowel sounds to his captor. At the same time a voiceover reveals, “With a gun barrel between your teeth, you speak only in vowels.” He reveals how he came to find himself in the situation, suddenly realizing that everything “has got something to do with a girl named Marla Singer.” Instantaneously the flashback begins and the audience is thrown into the arms of Bob with the narrator. The audience depends on Jack to truthfully relay his experiences, connecting his aural story harmoniously with the events presented onscreen. In this case, the audio and visual do not always match up, as Jack’s narrative often contains loopholes, until the end when the audience is informed that Jack and Tyler have been the same person all along. A reflection back on the film after the information is divulged allows the viewer to appreciate the exploitation of noir techniques combined with Fincher’s commercial style to radicalize the familiar genre.

Even though Jack and Tyler are actually the same person, they are presented as two halves of a warring whole, symbolizing the duality of all man. The once one-man noir hero has been split into two, dividing conflicting sides of a complete person. Grevin considers how “noir films present us with masculine heroes in whom divided natures wage war.” The men in Fight Club psychically split that divided nature. They each embody completely different values and ideals. They are also separated psyches: “In David Fincher’s Fight Club, Tyler (Brad Pitt) and Jack (Edward Norton) embody the id and the superego of the film’s narrator/hero” (Thompson). Tyler is the incarnation of Jack’s untamed desires, while Jack himself (initially) closely follows the social code. Jack is consumed with material possessions with a home fully furnished with pieces from IKEA, whereas Tyler lives in a dilapidated house with no power, electricity, or clean water. One scene, the phone call between Jack and the detective from the Arson Unit calling about Jack’s burnt-down condo, demonstrates the differences between the two protagonists. As Jack learns from the detective that a homemade bomb caused the explosion, his indifference becomes apparent. Tyler enters the scene, aware of the call’s matter, and instigates Jack’s reactions. As his subconscious incarnate, Tyler recites, “Reject the basic assumption of civilization, especially the importance of material possessions.” Jack acts enraged at the idea that his indifference potentially marks him as a suspect: “That condo was my life. OK? I loved every stick of furniture in that place. That was not just a bunch of stuff that got destroyed. It was me!” However, Tyler represents everything Jack wishes to be. Although he lives in a materialistic world, attached only to those belongings he dreams of giving it all up and starting a new, more exciting life. This goes so far as to his creating an alter ego without the awareness that Tyler is not real. Throughout it is unknown that Jack and Tyler are actually the same person, so it easiest to allow them to assume the role as two separate entities. As the narrator, it is expected for the audience to sympathize with Jack. But as the “always complex relationship between two male protagonists played by two male stars of commensurate stature, who therefore demand equal attention and narrative importance,” equal attention must also be given to Tyler (Grevin). Jack is only the narrator because Tyler is not, although Tyler controls the actions of most scenes, creating conflict between the aural narrator and his visually leading counterpart. Their existence is wholly dependent on one another. The end scenario and accompanying flashback is based on the idea that Jack and Tyler are purely relational, and reliant on their differences. Tyler cannot exist without Jack, as Tyler is a figment of Jack’s imagination. However, without the creation of Tyler, Jack would continue a mundane life of condiments and IKEA home furnishings. Their duality, their warring conflict between consumerism and anti-consumerism, alludes to the American Dream so heartily critiqued in noir.

Although Fincher investigates the concept of the double protagonist in Se7en as well, he employs noir elements not seen in his later film, Fight Club. Everything Fight Club is missing to immediately peg it as noir can be found in Se7en. Detectives Somerset and Mills investigate the intricate murders of John Doe, heavily based on the seven deadly sins. Thanks to Somerset’s intellect and research, the two are able to botch John’s immediate plans; however, this causes more trouble for the duo. Somerset and Mills have problems as is, the film taking place days before Somerset retires as Mills recently transfers to his new unit. Everything about Somerset and Mills are opposites: one is an older black man who has seen too many bad things to keep hope for mankind; the other is a spritely young white man who requests a transfer to a crime-infested neighborhood with the hope of doing some good in the world. While Somerset has lived a life (mostly) alone with no wife or children, Mills has a beautiful supportive wife carrying child (although Mills does not know this until the end) and dogs he treats as his babies. It seems that they are completely dissimilar. However, the characters in these films “demonstrate the merging of the two central males into one; the males are always complementary halves of a dyad that suggests not two individuals but two warring halves of one consciousness, a psychic doubling…” (Greven). In spite of how different Somerset and Mills are, they work together to solve the case. Combined, they make the best force, the best cop, to pin up against the intricate patience of John Doe. While Somerset relies on research, spending hours pouring over Dante’s Inferno and The Canterbury Tales, Mills takes action despite the consequence. They only take on these roles in relation to the other. One is logic because the other half is passion. Without each other, these characters would be incomplete. David Fincher explores the two sides of every person by making each side its own entity and coercing them to interact. This separation of a whole, the double protagonist, must make the viewer reconsider his vision of the noir hero, and even the femme fatale. By splitting the hero into two protagonists, Fincher has inadvertently removed the femme fatale from Se7en. Mills’ wife loves him, will do anything for him. Even though she [technically] brought him down, it was her murder, not her own actions, which affected Mills’ decision to “become wrath” and kill John. While the film is set up as an obvious neo-noir, Se7en reflects the historical changes and modern societal fears, and therefore the genre specifications associated with noir film.

David Fincher employs classic noir techniques alongside fresh sign-systems and innovative character dynamic to continue to help the genre adapt to the changing social conditions. As time changes, genre changes. Directors like Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and David Fincher, with their auteur filmmaking, help develop these ever-changing genres to withhold the core values of the genre (or in some cases mock them) and adjust the conventions to fit the new meaning of the genre. Fincher is one of several filmmakers who have contributed to the neo-noir, creating new cult classics and reviving gritty realism as an aesthetic.

Works Cited

Dussere, Erik. “Out of the Past, Into the Supermarket.”Film Quarterly 60.1 Fall 2006. 16-27. JSTOR. Web. 13 Jul 2011. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2006.60.1.16>.

Greven, David. “Contemporary Hollywood Masculinity and the Double-Protagonist Film.” Cinema Journal 48.4 (2009): 22-43. Project MUSE. Web. 22 Jan. 2011. <http://muse.jhu.edu.libproxy.sbcc.edu:2048/>.

Lindsay, Sean. “David Fincher.” Senses of Cinema 27 n. pag. Web. 05 Jul 2011. <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2003/great-directors/fincher/>.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “New Are Noir,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 07.24.11 / 2pm

- Category:

- Academic Papers, DVD, Films

1 Comment

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]