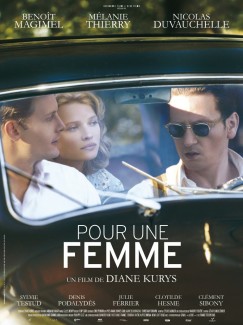

For A Woman (Pour Une Femme) (Diane Kurys, 2013): France

Reviewed by Daniel Chein. Viewed at SBIFF.

Leafing through the 2014 program, I was a bit overwhelmed by the variety of different films being screened at this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival. Being my first festival (and my first review), I was self-conscious about my decision-making process: how do you decide which film to watch? Do you base your choice on the one sentence synopsis? Or perhaps the genre and the mood you’re in? Maybe it should be as simple as finding the film whose screening time best suits your schedule… After what seemed to be an hour of flipping pages back and forth (a process not entirely different from scrolling down Netflix), I finally ended up going with a French Drama titled For A Woman (Pour Une Femme). As someone who speaks no French and has a very limited exposure to contemporary French films, my preconceptions were, sadly, solely based on the film’s title, which reeked of a sappy, romantic fragrance. But director Diane Kurys had something in store that completely took me by surprise in the best possible way.

Drawing from her own life experiences, Kurys’ story unfolds through a subtle interplay between the present and the past of a family’s history spanning two generations, set in the 1980s and 1940s respectively. In the present, Anne (Sylvie Testud), a screenwriter and the younger of two sisters, becomes absorbed into her parents’ past as she is sorting through her deceased mother Léna’s (Mélanie Thierry) belongings. Among the remains, she comes across a man’s ring that she couldn’t imagine belonging to her father Michel (Benoit Magimel): who then, did it belong to? Anne’s father was still alive, but was always dismissive whenever Anne inquired about his story. She knew, for example, that he was a Russian immigrant, a communist Jew, and had a brother named Jean (Nicolas Duvauchelle), but never knew how he arrived in France or what happened to her uncle. Compelled by how little she actually knew, Anne begins to dig deeper into her family’s past, searching for the intangible memories–that would in turn inform the story for her new screenplay–elicited by the dated articles and dusty photographs left behind. Kurys then transports us in a time machine to postwar France as the film plays out through the perspectives of Michel, Léna, and Jean.

For a Woman has all of the key elements that make a compelling film. The story pulls you in as you’re put in Anne’s shoes and explore the imaginary past through tangible evidence left in the present. The characters are portrayed in a way that the viewer can empathize with their perspectives and values. The backdrop of postwar France lends itself to interesting plot points over which tension between the characters is built through their conflicting wants and needs. The film is very moving, striking an emotional chord with a psychological realism harking back to the New Wave. To brighten up the sometimes heavy moments, the script employs tasteful humor that complements the heartfelt drama. And the film touches on many different themes: familial piety and loss, the political divide, and, of course, romance and love, to name a few. I don’t want to spoil the film for those who have yet to see it, but to sum up, Kurys’ For a Woman is not to be missed. Don’t judge this film by its title: its content is much deeper and richer than the title might suggest!

About this entry

You’re currently reading “For A Woman (Pour Une Femme) (Diane Kurys, 2013): France,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 02.01.14 / 10pm

- Category:

- Films, Santa Barbara Film Festival 2014

7 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]