Puberty with Fangs: The Teenage Exploitation Film

Paper by Reid Sailer. Viewed on DVD.

The Golden Age of the Hollywood Studio System was dying. The ruling of the 1948 Supreme Court case, “United States v. Paramount Pictures Inc.”, often shorthanded to the “Paramount Decree”, resulted in the demolition of the business model that the five major studios had thrived on for the past twenty years. As a result, the death of Vertical Integration in the system allowed for the rise of independent producers who were no longer under the thumb of the major studio heads and their powerful influence. One of the prime examples of this new wave of independent film productions was the American Releasing Corporation, later known by 1956 as the American International Pictures. Headed by James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff, the two found massive success in lowbudget genre films for a teenage audience. While the inception of the exploitation film predated AIP, the studio certainly spearheaded the innovation of selling cheap, sensational, and shameless pictures to the nationwide market, (Cook).

The Golden Age of the Hollywood Studio System was dying. The ruling of the 1948 Supreme Court case, “United States v. Paramount Pictures Inc.”, often shorthanded to the “Paramount Decree”, resulted in the demolition of the business model that the five major studios had thrived on for the past twenty years. As a result, the death of Vertical Integration in the system allowed for the rise of independent producers who were no longer under the thumb of the major studio heads and their powerful influence. One of the prime examples of this new wave of independent film productions was the American Releasing Corporation, later known by 1956 as the American International Pictures. Headed by James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff, the two found massive success in lowbudget genre films for a teenage audience. While the inception of the exploitation film predated AIP, the studio certainly spearheaded the innovation of selling cheap, sensational, and shameless pictures to the nationwide market, (Cook).

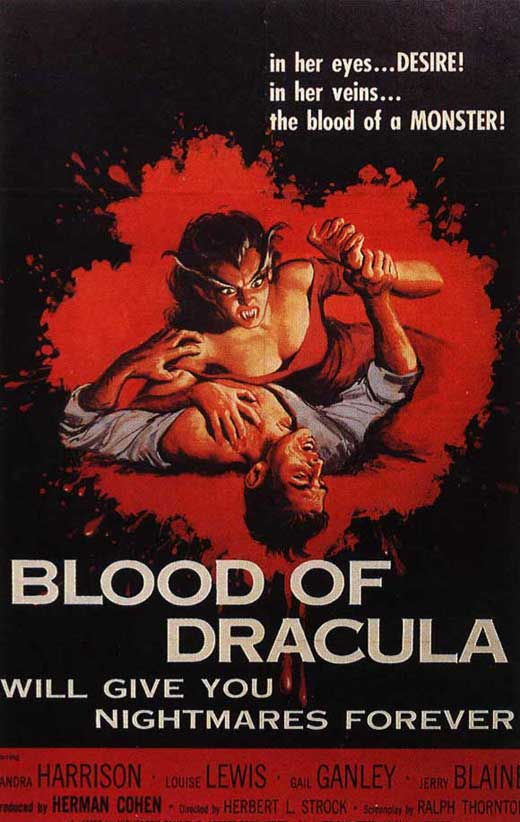

The Bmovies that AIP produced were created as quick cashins that were meant to entertain in terms of action, scifi, horror, or comedy often shown as double bills. Considering that AIP’s audience varied from teenagers to young adults, it became a conscientious decision to focus on teenage protagonists for a number of their films. This sparked a new version of the subgenre, “Teensploitation” or “Teenpics”; where the film’s focus became less about educational but instead changing to genre pictures that revolved around a cast of young characters who were depicted as either ideal and wholesome or defiant, angsty and troubled often toting an antiadult authority undertone. The latter characterization is what drove the horror pictures, including; I Was A Teenage Werewolf (Gene Fowler Jr., 1957), I Was A Teenage Frankenstein (Herbert L. Strock, 1957), Blood of Dracula (Strock, 1957), plus the meta and selfaware, How to Make a Monster (Strock,1958). AIP used the expanding popularity of the Bmovie to exploit the growing public anxiety towards budding teenage culture through a horror themed analogy of fearful adults who wished to mold and control the rebellious teenager into a model representation of American values; thereby mocking the notion that teenagers who did not conform to society standards meant that they were embracing their “monstrous” side and would never be able to become happy and successful adults.

The teenagers of the 1950’s were caught at an impasse; despite preceding the infantile generation created by the postwar Baby Boom, teens were caught inbetween generations where they were marginalized by adults. Suburban life became the normality and families spent their evenings watching the latest technological innovation, the television, which was quickly replacing the movie theater as the goto form of entertainment: “There were a few television shows aimed at young children, nothing for teenagers, and nothing on the radio speaking to teen life. Teenagers felt left out, ignored, disenfranchised”. Teenagers found validation among each other in the form of common social gatherings like sockhops and trips to the mall, as well as shared interests in popular rock n’ roll music, dances, drivein movies, and an exploration of sexuality. This was the turning point where the adults began to condemn teenage activity and values by laying down a series of rules and restrictions, thus widening the gap between the generations, (Powers).

“A movie is said to ‘exploit’ an audience when it reflects on screen the audience’s expectations and values,” (Doherty 5). The friction between the teenager and adult authority, is best exemplified in AIP’s 1957 film, Blood of Dracula, the genderswapped version of the more famous, I Was A Teenage Werewolf. Where in Teenage Werewolf the tension between the main character Tony and his girlfriend’s father is considerably tense due to Tony’s triggered temper, Blood of Dracula’s opening scene quickly establishes an explicit understanding of why neither Nancy (Sandra Harrison) nor her parents respect each other.

“You sell the house, you yank me out of school, you broke up my whole social life,” “You mean those moonlight beach parties? And those rock and roll sessions?”

In the film’s opening we learn that Nancy’s father, a widower of just six weeks, has

already remarried a presumably younger and lascivious woman who openly detests his daughter. Nancy is furious and outwardly antagonistic towards both of them, displayed by her smoking and attempt to crash the car, because of how miserable she finds the situation to be. She sees herself as the last string to her family, and now that her mother is gone and a new wife is here, she is no longer needed by her father and therefore no longer has a family. This isn’t helped by her parent’s plan to send her to a preparatory school, essentially ridding themselves of their problem a statement reinforced by the stepmother in the dialogue. Nancy’s distress perfectly explains her behavioral problems, which makes it hard for the audience not to sympathize with her, as her situation makes her one of the more relatable and wellwritten characters in any of these Teenage Monster films that AIP produced.

This can be attributed to scriptwriter Aben Kandel, who used various alias such as Ralph Thorton and Kenneth Langtry during his tenure with AIP (IMDb). All of these monster films were written by Kandel and Herman Cohen, who seem to have used I Was A Teenage Werewolf as a base point for Blood of Dracula to reshift the former film’s misstep of focusing too long on the adult characters at the expense of the teenage hero. Not only does Nancy get an unambiguous motivation, unlike Tony from Teenage Werewolf, but by setting the film at a boarding school, this allowed for further dynamic interaction between the teenage and adult cast.

The movie establishes a theme of negligence both on the part of Nancy’s parents and the faculty in that neither truly understands Nancy’s feelings towards her forced enrollment and later the doomed experiment that turns her into a vampire. This experiment, conducted by Miss Branding (Louise Lewis) and a cursed amulet, is exactly a recreation of the experiment from Teenage Werewolf that has basically the same results. This makes the film rather uncreative by having the same kind of Frankensteinesque mad doctor in both films, not to mention an actual Dr. Frankenstein in I Was A Teenage Frankenstein, who all use a teenager as a guinea pig for their questionable pursuit of scientific superiority. However by putting a woman into the shoes of the mad doctor, Blood of Dracula tackles a gendered approach on the subject of obtaining power:

“I can release a destructive power in the human being that would make the split atom seem like a blessing. And after I’ve done that, after I’ve demonstrated clearly that there’s more terrible power in us than man can create, scientists will give up their destructive experiments. They’ll stop testing nuclear bombs. Nations will stop looking for new artificial weapons because the natural ones, we the human race, will be too terrible to arouse.”

These words spoken by Miss Branding, while similar to the speeches made from the doctors of the other films, has more gravitas due to her gender. She isn’t just determined to prove her theory about the destructiveness of mankind’s primal instincts, but she needs to prove herself as a woman in the maledominated field of science. In hindsight this could be paralleled to the reallife struggles that scientist Rosalind Franklin faced when her work on the DNA structure was undermined by the pair, James Watson and Frances Crick, who used Franklin’s data to publish their findings which sent them into scientific prominence while she died without any recognition for her contributions (Kelley).

The DNA structure discovery occurred four years prior to Blood of Dracula’s release and actually gratifies Miss Branding’s motivation in the film more so than her male counterparts. She already has a handicap due to her gender, but to be a working woman who has neither a husband or children and is also not working in the clerical, service industry, or assembly line as 70% of women in the 50’s were doing, she really does have a lot of pressure relying on her scientific discovery (Beer). Neither Nancy or Miss Branding conform to the expectations that are placed on them as a teenage or adult woman. Miss Branding though, who often sits in shadows contrast to the brightness that the teens are shown in, means to correct Nancy who she sees as “a natural fire with explosiveness close to the surface…a disturbed girl”.

The fact of the matter is that Nancy isn’t disturbed, she is just a teenager. She comes off as contempt and offput by those around her but that can simply be explained by her extreme unhappiness of being removed from her social circle and school to be put into a new environment that she isn’t familiar with. By the adult authorities she is seen as misbehaved but by her classmates she’s described as having “spirit” due to her assertive nature. She’s not only dresses normally, presents herself as wellread and spoken, she engages in social activities with ease, such as the inprompt dance in the girl’s dormitory and later a scavenger hunt. It is the effect of being experimented on and being told that she does have a problem that she is not normal that truly ignites the monster from within. But instead of taking it out on the adults who have incorrectly characterized her, her vampiric nature results in her attacking her own teenage peers.

At the expense of exploring vampire lore and interweaving it within the context of adolescence, Blood of Dracula does not make great use of its titular monster. Here even the title comes into question as Dracula himself is never mentioned, “(just a Transylvanian amulet that might have had something to do with him),” (Skal 258). Once again the comparisons between Blood of Dracula and I Was A Teenage Werewolf become apparent when the monster finally appears on screen. Not only are the makeup effects rather similar, although the vampire is granted additional lower fangs reminiscent of a snake and wildly exaggerated eyebrows, but how they transform and present themselves to their victims are practically identical. Aside from the nocturnal nature that vampires are known for, the fact that the film’s creature has to be a vampire is mostly irrelevant. Common vampiric traits such as shapeshifting, hypnotism, a lack of reflection, or the ability to change other people into vampires is all lost here. Nancy’s vampire snarls and bites and does little else.

It is the influence of Miss Branding and her amulet that gives the movie tension as the viewers are allowed to see the repercussions that this is having on Nancy. She can’t remember certain things, she has terrible nightmares, and can’t even wake up on her own accord without Miss Branding commanding her. The essence of this control is seen during the party scene, where Miss Branding, sitting in shadow brandishing the amulet, stares daggers through the window into the dormitory, knowing that she is manipulating Nancy. The girl begins to feel unlike herself and realizes that she is losing control over her own body. This is capitalized on in the penultimate scene where Nancy’s boyfriend Glenn (Michael Hall) visits her:

“I’m sick. I’m worried sick about you…about both of us. All those wonderful plans we made; going to state college together, then after that, the other plans.”

“Kids make plans. Dream stuff.”

Glenn, representing the stability and happiness Nancy once knew, has come to check up on her in the wake of the murders happening. She outright rejects him and behaves coldly towards him, knowing that she is succumbing to the vampire lust for blood and need to kill. At this point she has killed her peers and deceived the police, so she realizes that her one last connection to her humanity is not enough to save her as she’s too far gone. She pushes herself away from him before she has the chance to sink her fangs into him, yelling at him to get out of here and leave her to suffer. This transitions into the final scene where monster and creator clash, ending in tragedy for our heroine.

In a 1954 article about teenage delinquency, psychologist Robert Linder stated, “The youth of the world today is touched with madness, literally sick with an aberrant condition of mind.” (Oakley). The characters of the AIP monster films are the worst versions of Linder’s quote. The natural behaviors of a teenager are manifested through a senseless, bloodthirsty monster, suggesting that Nancy or Tony were doomed from the beginning as neither were able to control their perfectly natural teenage instincts and were therefore punished for embracing their inner monster. Even when their characters realize in their respective films that they want to be “normal” and accept the rules and regulations that are expected of them, they are too late to save themselves.

Herman Cohen would take this method of “mixing juvenile delinquency with atomicage takes on old horror tales” across the pond but ultimately found success in America as this odd subgenre begot every form of monster from Dr. Jekyl to zombies to ghosts (Marriot 71). It’s not surprising as these films were cheap to make, as seen by the lowquality productions and static cinematography, signifying that the Golden Age of film was lost by the late fifties and wouldn’t be remet until the New Hollywood era of the late 60s. Interestingly, the reception of Blood of Dracula does not match I Was A Teenage Werewolf despite the series of similarities, not entirely mentioned here; however it contributed to one of the many vampire films that would reignite the interest in fantasy horror during a time when nuclear war phobias were much more prominent (65).

The teenage subculture embraced the ridiculousness of these movies, making the “I was a teenage [noun]” concept a staple in pop culture. The metaphor of monsters representing adolescence and puberty would continue to be used for great effect in later films such as 1987’s The Lost Boys and 2000’s Ginger Snaps. The need to gain control over reckless teenagers has remained constant through history, although there has been a greater effort to understand and communicate with teens and adults. That being said, it could be argued that while fifty years has changed perception on what it means to be a teenager there is still a constant fear of what teenagers represent for the future that make them as terrifying as ever.

Work Cited

● “Aben Kandel.” IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

● “American International Pictures.” House of Horrors. Internet Zombie Productions, 1997.

Web. 15 Nov. 2014.

● Baumann, Marty. “Blood of Dracula.” THE ASTOUNDING B MONSTER | HORROR.

N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

● Blood of Dracula. Dir. Herbert L. Strock. Perf. Sandra Harrison, Gail Ganley, Jerry

Blaine, and Louise Lewis. American International Pictures, 1957.

● Cook, David A. (2000). Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate

and Vietnam, 1970–1979. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California

Press

● Doherty, Thomas Patrick., and Thomas Patrick. Doherty. “1: American Movies As A

LessThanMass Medium.” Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American

Movies in the 1950s. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1988. N. pag. Print.

● “Film Reference.” The Exploitation Explosion. Advameg, Inc, n.d. Web. 10 Nv. 2014.

● J. Ronald Oakley, God’s Country : America in The Fifties (New York : W.W. Norton,

1986), p. 270.

● “The Hollywood Studios in Federal Court The Paramount Case.” Hollywood Renegade

Archives. The SIMPP Research Database, 2005. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

● “Herman Cohen.” IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 14 Nov. 2014.

● I Was A Teenage Werewolf. Dir. Gene Fowler. Perf. Michael Landon and Herman Cohen.

American International Pictures, 1957.

● I Was A Teenage Frankenstein. Dir. Herbert L. Strok. Perf. Gary Conway and Whit

Bissell. American International Pictures, 1957.

● Kelley, Shana O. “A Milestone for Science, and for Women.” The Boston College

Chronicle. N.p., 13 Feb. 2003. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

● Lewis, Jon. “”Reinventing Hollywood”” American Film: A History. New York: W.W.

Norton, 2008. N. pag. Print.

● Marriott, James, and Kim Newman. “Chapter 5: The 1950s.” Horror!: 333 Films to Scare

You to Death. London: Carlton, 2010. N. pag. Print.

● “Opportunities for Women in 1950s.” Omeka RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

● Skal, David J. “Chapter 7.” Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel

to Stage to Screen. New York: Norton, 1990. 25859. Print.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Puberty with Fangs: The Teenage Exploitation Film,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 12.05.14 / 8pm

- Category:

- Academic Papers, Films

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]