The Dilemma’s of a Cameraperson

Paper by Lia Durham.

Films reflect how we see the world, they are our stories told from other people’s perspectives. Audiences can relate to the characters they see on the screen and if a film does it’s job successfully the audience will be able to connect to some aspect of the story. This is not just true for fictional films but documentary films as well. The difference is that in documentaries the characters are actually real people and their stories are true from their actual experiences. A documentary filmmaker has the job of presenting someone’s story in a way for the audience to care. They need the audience to want to keep watching, so in order to do this it is up to them to create the most compelling story with what they are given. Sometimes this means asking a lot of the subject in their willingness to be open and honest to serve the film. In Kirsten Johnson’s “director’s statement” for Cameraperson (2016), she states, “I ask for trust, cooperation and permission without knowing where the filming experience will lead”. She also states that “I know little about how the images I shoot will be used in the future and can not control their distribution or use”. In these passages, Johnson underscores how much responsibility the filmmaker has to their subject since they are the ones presenting this person’s story to the world it is up to them to create a safe space for the subject to be open while ultimately staying true to the story and where that leads. By analyzing the relationship between filmmaker and subject in relation to key sequences in Cameraperson and key points made in Bill Nichols’ “Introduction to Documentary” I will examine how the subject is really putting their life’s story in the hands of the documentary filmmaker and the filmmaker must respect that trust without having it compromise the story.

Films reflect how we see the world, they are our stories told from other people’s perspectives. Audiences can relate to the characters they see on the screen and if a film does it’s job successfully the audience will be able to connect to some aspect of the story. This is not just true for fictional films but documentary films as well. The difference is that in documentaries the characters are actually real people and their stories are true from their actual experiences. A documentary filmmaker has the job of presenting someone’s story in a way for the audience to care. They need the audience to want to keep watching, so in order to do this it is up to them to create the most compelling story with what they are given. Sometimes this means asking a lot of the subject in their willingness to be open and honest to serve the film. In Kirsten Johnson’s “director’s statement” for Cameraperson (2016), she states, “I ask for trust, cooperation and permission without knowing where the filming experience will lead”. She also states that “I know little about how the images I shoot will be used in the future and can not control their distribution or use”. In these passages, Johnson underscores how much responsibility the filmmaker has to their subject since they are the ones presenting this person’s story to the world it is up to them to create a safe space for the subject to be open while ultimately staying true to the story and where that leads. By analyzing the relationship between filmmaker and subject in relation to key sequences in Cameraperson and key points made in Bill Nichols’ “Introduction to Documentary” I will examine how the subject is really putting their life’s story in the hands of the documentary filmmaker and the filmmaker must respect that trust without having it compromise the story.

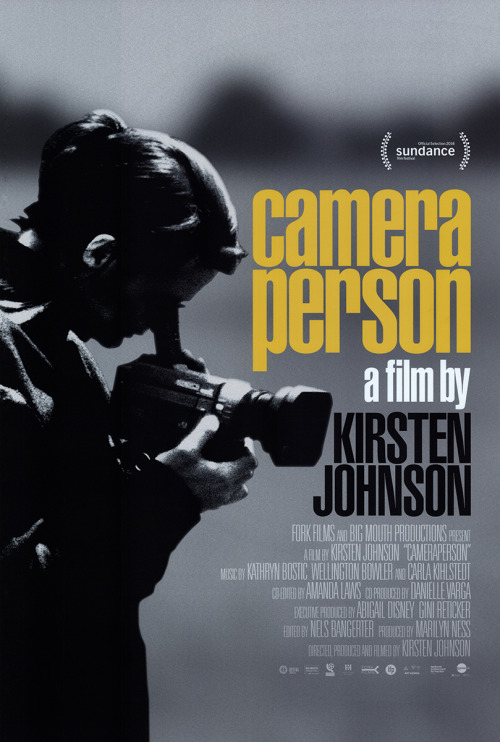

Kirsten Johnson’s film Cameraperson is a documentary film about her work filming documentaries. As a cameraperson Johnson has traveled the world working on other people’s films. During that time she has encountered many different people and many different stories and Cameraperson is her memoir about the certain experiences that have stayed with her. In order to make the film she reached out to the past directors she has worked for over her illustrious career and has edited together the film based off of actual footage she has filmed. This allows Johnson, for once, to have a say in the aftermath of what she films. During the interview for Cameraperson In the Service of the Film one of the director’s she has worked with in the past, Gini Reticker, commented on a scene in Cameraperson. Reticker noticed that one of the shots was from the shooting of her movie but she never used it in the cut of her film and really doesn’t remember it that much at all. Johnson on the other hand loves the shot. She is passionate about how she used the camera in a fluid motion to follow one person to another to another like a beautiful dance. This goes to show that even though Johnson as the cameraperson could shoot something exquisite and amazing when it comes down to it she has no say in what makes the cut. That is one aspect of what makes Cameraperson so interesting, Johnson now has the power in the editing room. The documentary falls under Bill Nichols’ performative mode. We are aware of Johnson as the filmmaker and understand that these shots are from her point of view. We are less concerned with the actual information of what she is shooting and more concerned with what it was like for her to shoot it. The tone and mood of the footage is the most important aspect of the film.

In “Introduction to Documentary” Bill Nichols asks the question “How should we treat the people we film?” (13). This question is a reminder that there are numerous ways in which documentary filmmakers can choose to represent their subjects. Nichols’ points out an easy way to think about the relationship. It’s the verbal formulation: “ I speak about them to you ” (13) . This is the most common way documentaries are formatted. The “ I ” is the filmmaker, “ them ” is the audience and “ you ” is the subject of the film. This formula however creates a separation between the subject and the audience handing over all the power to the filmmaker. The subject has to trust the filmmaker with their story and relinquish control on how it will be presented to the audience. This can create feelings of apprehension and mistrust and it is the filmmaker’s job to ease these feelings of concern.

In Cameraperson we can witness the level of care she puts into trying to make people feel comfortable. During some b-roll shots of a town in Bosnia we hear Johnson talking off screen to what can be assumed is a producer about public domain. Johnson explains that if you are shooting in public you don’t need to get permission from everybody who walks into the frame. However Johnson says “I always try to have some kind of relationship with people, like I’ll look them in the eye like “You see me shooting you, don’t you?”” This shows how mindful she is of the people she is filming. Even if they are not the subjects of the film she still wants to be respectful of the environment she is in because for the most part she is a guest in the community.

In the roundtable interview Cameraperson In the Service of the Film Johnson discusses a scene in Cameraperson where she and the sound person, Judy Karp, walk to a cemetery in Bosnia with a woman who survived rape. She is going to the cemetery to visit her husband and sons’ graves and instead of just “getting the shot” and leaving Johnson and Karp stayed with her and shot the entire event. They both knew that they wouldn’t use all of the footage in the final film but it was more important to show the woman that they were there for her. Johnson does not believe in the mentality of just going somewhere to get something for the film, she is more concerned with connecting with people. Ultimately this connections does get the filmmakers more of a real moment. By building real connections the subjects are more likely not to “act” for the camera and therefore the cameraperson can capture a more truthful experience.

It’s a give and take relationship between filmmaker and subject in documentary films. This relationship is also voluntary. Subjects are not forced to be in films, they sign waivers, they agree to the filming and the intrusion in their lives. Even though they are willing participants it is important for filmmakers not to take advantage of their generosity. What Johnson clearly excels at is creating relationships with the people she is filming. This overall seems to create a better working environment for everyone involved. It also creates a better opportunity for the deeper truth to arise. When people feel safe and comfortable they open up. As a documentary filmmaker your job is to tell the audience someone else’s story and for that to happen in a successful way the filmmaker and subject must create trust and maintain it throughout the filming process.

Bibliography

Johnson, Kirsten. Cameraperson . USA. Big Mouth Productions, 2016. Film. Johnson, Kirsten. Cameraperson In The Service Of The Film . 2017. TV.

Nichols, Bill. Introduction To Documentary . 1st ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010. Print.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “The Dilemma’s of a Cameraperson,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 07.25.17 / 4pm

- Category:

- Academic Papers, Films

14 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?]