Demystifying the Samurai

Paper by Audrey Carganilla.

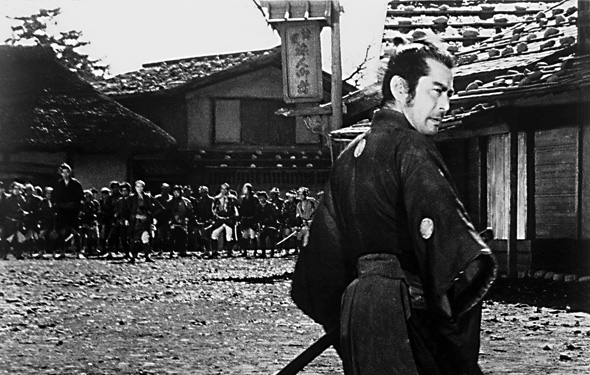

To put it simply, Akira Kurosawa is a director with a far East style with the spirit of the Wild West. He is one of the most recognizable Japanese filmmakers to not only American audiences, but globally. His style consists of masterfully shot compositions that add depth and character to every frame, and manages to use up the negative space with movement artfully and purposefully. When a person hears “Akira Kurosawa”, immediately they would correlate the name to “samurai” because given a career that spanned almost 60 years with 30 films under his belt, his most well known works gravitated around these formidable soldiers. Kurosawa tends to intertwine three common themes in his films: the representation of men, social structures, and violence. In Rashomon (1950), Seven Samurai (1954), and Yojimbo (1961), these themes are used to examine the role the concept of masculinity plays into Japanese cinema with the help of Akira Kurosawa’s expertise in storytelling through composition and characterization. This is relevant because of Kurosawa’s permeating inspiration and ability to create a bridge between the East and the West through film, and we see that influence in films such as The Magnificent Seven (Sturges, 1960) and Star Wars (Lucas, 1977).

To put it simply, Akira Kurosawa is a director with a far East style with the spirit of the Wild West. He is one of the most recognizable Japanese filmmakers to not only American audiences, but globally. His style consists of masterfully shot compositions that add depth and character to every frame, and manages to use up the negative space with movement artfully and purposefully. When a person hears “Akira Kurosawa”, immediately they would correlate the name to “samurai” because given a career that spanned almost 60 years with 30 films under his belt, his most well known works gravitated around these formidable soldiers. Kurosawa tends to intertwine three common themes in his films: the representation of men, social structures, and violence. In Rashomon (1950), Seven Samurai (1954), and Yojimbo (1961), these themes are used to examine the role the concept of masculinity plays into Japanese cinema with the help of Akira Kurosawa’s expertise in storytelling through composition and characterization. This is relevant because of Kurosawa’s permeating inspiration and ability to create a bridge between the East and the West through film, and we see that influence in films such as The Magnificent Seven (Sturges, 1960) and Star Wars (Lucas, 1977).

In Kurosawa’s films, there were various and distinctive ways that men were represented. In Rashomon, the audience is exposed to four different and contradicting tellings of the same affair of murder and rape and in this story, there are three figures, the samurai, the samurai’s wife, and the bandit. In each character’s respective hearings, they are of course, biased towards themselves. The samurai commits suicide, the wife becomes a victim, and the bandit falls for seduction. Through each character, they try to present themselves in the most favorable light to avoid punishment, yet when we hear from an actual witness, the woodcutter, we hear a tale of a pitiful and fearful encounter. The samurai, originally seen as a reserved but strong man, and the bandit, a loud and aggressive man, were revealed to be everything but. The archetype of the samurai is often associated with being virtuous, yet we see the opposite in Rashomon and even in arguably one of Kurosawa’s most critically acclaimed film, Seven Samurai. Although there are several male characters in this film, the most telling characters would be the elder samurai Kambei and the abrasive Kikuchiyo. With Kambei, he is a composed and experienced leader that represents the ideal samurai who fend for those that cannot do it themselves, even if there is no apparent reward or laurels to be given. On the other end, there is Kikuchiyo who is somewhat similar to the arrogant bandit in Rashomon that is also played by Toshiro Mifune, that wants to be recognized but also has a need to prove himself and rise above his origins, while at the same time, defending it. “Japanese Cinema: Film Style and National Character” by Donald Richie highlights the story of Seven Samurai and says “It is concerned with the present, though its story is laid in the past. It criticizes contemporary values but insists that they are, after all, human values” (232). Each of the seven samurai have such distinct characteristics that were explored in the three and a half hour long runtime that show that there is no one way to “be a man”. In Yojimbo, we get a character who is in the middle. Sanjuro stumbles across a strip of a town that is split into two because of a turf war and tasks himself to settle it once and for all. While he does has moments of charitability such as saving a family that was caught in the midst of the action, he was mostly trying extort the most money he could from the two gangs before leaving. Even though he sticks around because he finds it amusing, Sanjuro does stick to his word in the end. In all three films, we see both the “good” and the “bad”, but more importantly, there is this sense of the ambiguous nature of man and morality.

By watching these films, we also get a sense that the structure of society doesn’t really allow for all men to be equal. With Yojimbo, if you are not apart of either gang, you are a non factor such as Gonji, the owner of the shop that Sanjuro frequents but no one else. If someone does not choose a side, they lose the benefits of business from each side so it is best to affiliate one’s self with either one even if that means compromising one’s integrity. The anarchical nature of this system is representative of the overbearing force the gangs have on those that have no power, the common people. The book, “The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa” by Stephen Prince says that “The power of the social structure manifested a malevolence that could undermine and destroy the efforts of the heroes” (200). In the case of Rashomon, we see this to be true. Abhineet Kumar wrote an article titled “Rashomon – Subjectivity and Class” in which he discusses how society also happens to have role in the film’s ultimate themes of truth and humanity as a “catalyst for dishonesty.” As the samurai, the wife, and the bandit all have contradicting stories that only serve to make them look better, Kumar suggests that it is due to “their own standards or by those of feudal Japan – a society governed by strict social hierarchy in which citizens were bound to the roles they were assigned.” Their efforts to clear their image end in vain with the woodcutter’s perspective, that holds the least bias and most value to the court. Similarly, in Seven Samurai, Kikuchiyo reveals the true nature and flaws of the caste system. We learn that Kikuchiyo is not of samurai status but born into the farmer’s class after his outburst, so he understands why the farmers had to lie about being helpless and not having any supplies. Despite originally being part of this caste system, he berates farmers as being just as dishonest and murderous as any other samurai or bandit is, so he also throws this question back at the samurai: “But then tell me this: Who turned them into such monsters?” As feudal Japan had such a rigid and unfair social structure, the poor farmers had to find a way to defend themselves against everyone above them, even if that means lying to gain sympathy and turning to violence.

Violence is saturated throughout Kurosawa’s films. Given that these films all involve samurai, death is inevitable on either end of the sword. Samurai and ronin alike usually are put in life or death situations, but they are better equipped and better skilled than most as we see in Seven Samurai where they are hired to protect the farmers. Although we do not visibly see blood spilling, the movements and cuts of the camera adds to the adrenaline of all the action. The farmers with their spears and the seven samurai and their swords versus bandits on horseback filled the screen and kept the action going. In Yojimbo, we hear Sanjuro himself say that the town would be better off with these two factions dead and gone. He was met with the threat of death by poisoning and pointed at with a gun, but still powered through to finish his job. Rashomon’s used violence, or really the idea of violence, to mask the truth behind the murder and mask the dishonesty of those involved. The act of violence isn’t commended or romanticized, but rather is a necessity to survive during feudal Japan.

The representation of men, how men are seen in feudal Japan’s caste system, and how violence is always present in Kurosawa’s films all tie into the concept of masculinity and what’s more masculine than a samurai? Although in Kurosawa’s films, they deconstruct what it is to be a samurai where we see them not necessarily follow the “Bushido code” as most would believe, but act like what they truly are: human. The article, “To Cross Fire and Water: Akira Kurosawa and the Cinema of the Higher Man” by Andrei Burke also takes this into account and says “Rather than being mystified by an unbroken code and legendary godhood, the samurai in Seven Samurai are portrayed as flawed human beings who must respond when called upon to serve their fellow man.” In Kurosawa’s films, we do not see masculinity in being an unstoppable force, but rather when there is this sense of vulnerability. When Kikuchiyo passionately rants about the paradoxes of the caste system, when the woodcutter volunteers to take care of the abandoned baby, and when Sanjuro risks being exposed to save a family; crucial moments like these are when the audience understands that a man’s actions in these circumstances are what truly defines him and not the stereotypical ideas of what it means to be masculine today.

There is a staggering difference in how Asian men are seen in Eastern media over Western media, where Asian men are often times emasculated, yet we see the opposite in Kurosawa’s films. In Kurosawa’s films, we of course see the ever potent samurai who radiate charisma yet in American film and television, Asian men are seen as undesirable or unlikeable like the character Mr. Yunioshi from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Edwards, 1961) who was not even played by a Japanese man. There is also a “restriction” placed on what an Asian man can play in Hollywood where we rarely see Asian men present outside of being “the nerd”, a very desexualized and emasculated role. Thankfully, over the years with actors like Steven Yeun who plays Glenn from the hit television show The Walking Dead who are outspoken about the misrepresentations and lack of representation of Asian men, Hollywood is making strides towards a more diversified profile. As there are these complex, multidimensional Asian men show in Kurosawa’s films, it shows that it isn’t impossible for Hollywood to do the same in a country where they are the minority.

Famed director Francis Ford Coppola once said “Most directors have one masterpiece by which they are known, or possibly two. Kurosawa has at least eight or nine” (Burke). Given Kurosawa’s long lasting career and unique style of framing everything, it’s not surprising many of his films were recognized for their excellence. This talent is seen in the films Rashomon, Seven Samurai, and Yojimbo which covers the portrayal of men, their place in society, how violence is part of their lives, and how all of that culminates into an idea of what it means to be a man in feudal Japan. And while we get such rich representations of Asian men in Japanese cinema, we are still lacking such in the Western medium. Just as Akira Kurosawa bridged the gap between the East and the West around the 1970’s with his Western inspired films, hopefully three dimensional Asian characters translates into the Western world as well.

Works Cited

Burke, Andrei. “To Cross Fire and Water: Akira Kurosawa and the Cinema of the Higher Man.”

Phalanx, 26 Mar. 2016,

phalx.com/2016/03/26/to-cross-both-fire-and-water-akira-kurosawa-and-the-cinema-of-th

e-higher-man. Accessed 21 Jul 2017.

Kumar, Abhineet. “Rashomon – Subjectivity and Class.” The Butterfly Films, 11 Mar 2014,

www.thebutterflyfilms.com/rashomon-subjectivity-class. Accessed 21 July 2017.

Prince, Stephen. The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa. Princeton University

Press, 1991.

Richie, Donald. Japanese Cinema: Film Style and National Character. Doubleday & Company,

Inc, 1971. quod.lib.umich.edu/c/cjs/agc9004.0001.001/–japanese-cinema-film-style-and-national-character?view=toc. Accessed 21 Jul 2017.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Demystifying the Samurai,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 08.09.17 / 9am

- Category:

- Academic Papers, Films

17 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?]