Uncovering Iran: Revolution and Rebellion An analysis on Iranian life during and post-Revolution, through the film Persepolis

Paper by Nakiessa M. Abbassi.

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 brought on much hardship and confusion for the citizens of the country. In the blink of an eye, Iran’s leadership had suddenly changed, and with it bringing an entirely new set of rules to abide by. While the Revolution in Iran brought about violence and upheaval to the country, its citizens still tried to live their lives in the same fashion as before, even adopting Western culture. However, with harsh laws and indoctrination, it was difficult to have any semblance of freedom or free will. Persepolis (Vincent Paronnaud, Marjane Satrapi, 2007) is a landmark film in that it offers a different view of the Revolution – one that is not generally known or discussed. Persepolis is a highly political movie, rebellious in itself. It shows the downfalls of the Iranian government and lack of coordination. It is unsurprising to find that the film is still banned in Iran and a number of other conservative countries, in addition to Satrapi not being able to return to the country since the release of her graphic novel, the inspiration for her film. Persepolis is unafraid to demonstrate all of the horrible murders, torture, and strict laws that drove people to take drastic measures. Through the film’s fearless description of Iran and the Revolution, it brings to light the lives of the citizens during this time period, a factor oftentimes overlooked.

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 brought on much hardship and confusion for the citizens of the country. In the blink of an eye, Iran’s leadership had suddenly changed, and with it bringing an entirely new set of rules to abide by. While the Revolution in Iran brought about violence and upheaval to the country, its citizens still tried to live their lives in the same fashion as before, even adopting Western culture. However, with harsh laws and indoctrination, it was difficult to have any semblance of freedom or free will. Persepolis (Vincent Paronnaud, Marjane Satrapi, 2007) is a landmark film in that it offers a different view of the Revolution – one that is not generally known or discussed. Persepolis is a highly political movie, rebellious in itself. It shows the downfalls of the Iranian government and lack of coordination. It is unsurprising to find that the film is still banned in Iran and a number of other conservative countries, in addition to Satrapi not being able to return to the country since the release of her graphic novel, the inspiration for her film. Persepolis is unafraid to demonstrate all of the horrible murders, torture, and strict laws that drove people to take drastic measures. Through the film’s fearless description of Iran and the Revolution, it brings to light the lives of the citizens during this time period, a factor oftentimes overlooked.

The film creates an animated world that lacks any color, besides the few scenes from Marjane’s future, which offers a contrast from the past and present. The black-and-white serves as a testimony to “provide forms of truth that are emotional rather than factual”, while also making violence “more abstract and more interesting” (Nabizadeh 157). The choice of coloring (or lack thereof) creates a depiction of violence that contributes to the “banality that haunts modern images of violence” (Nabizadeh 157). Satrapi’s decision to do so demonstrates how we have been so accustomed to violence that depictions have become normalized. Using black-and-white animation forces us to view violence in a completely different light. This offers a new view of violence and allows the audience to become more engaged. Not only does the black-and-white serve to bring attention to depictions of violence, it underscores the horrors of Iran during the Revolution. Intense scenes fade to black, demonstrating utter defeat, hopelessness, or sadness. At the same time, joyous scenes are filled with light, such as scenes where Marjane speaks to God or spends time with her grandmother. These are meant to bring the audience’s attention towards a pivotal moment. Shading with various greys offers dynamic scenes, while still drawing all the attention on starkly contrasted characters.

Through its use of colorization, the film is unapologetically truthful, it does not hide anything or try to paint events in colorful metaphor, it displays the events for the world to see and understand. The black-and-white is used to call the audience’s attention and create contrast where color could not, a tool used to give better insights and understanding.

In one particular scene, the establishing shot opens on a crumbling Tehran, with buildings falling apart because of a recent bombing. And yet, cars are still driving throughout the streets and people walk on the sidewalks, seemingly unperturbed. In the opening shots of the film, a similar scene was shown without the destruction, which relates to this particular moment. It demonstrates the normality of the war and the common occurrence of bombings, which eventually led people to carry on with their day-to-day lives.

Later in the same scene, we see a silhouette of a man clearing rubble away from a destroyed building, while three women further in the background carry on with a conversation.

Later in the same scene, we see a silhouette of a man clearing rubble away from a destroyed building, while three women further in the background carry on with a conversation.

Through the characterization of the people’s attitudes directly following an attack, the environment in Tehran seems almost nonchalant about impending destruction. It has become so common to see these events taking place that no one seems to mind anymore, or at least it is no longer of highest importance. Life carries on, the people rebuild, and hope there will not be another attack. In other words, the war has become so ingrained in the people’s lives, it is no longer marked as a unique experience.

In addition to the destruction of their country, Iran’s citizens must determine how to survive in the new regime, while still keeping their sanity. Because Marjane, like any other rebellious teenager, wears a denim jacket, pins, and sneakers, she is made to be a target by the morality police, in this case, two women wearing chadors. This characterization is an artistic rendition of how these morality police were viewed, with long frames and harsh demeanors. An interesting aspect of their characterization is their snake-like poses, an explication of their evil atmosphere and seemingly sinister attributes.

In addition to the destruction of their country, Iran’s citizens must determine how to survive in the new regime, while still keeping their sanity. Because Marjane, like any other rebellious teenager, wears a denim jacket, pins, and sneakers, she is made to be a target by the morality police, in this case, two women wearing chadors. This characterization is an artistic rendition of how these morality police were viewed, with long frames and harsh demeanors. An interesting aspect of their characterization is their snake-like poses, an explication of their evil atmosphere and seemingly sinister attributes.

Their all-black chadors create the illusion of overarching power, and as Marjane is begging to be let go, the view pans down to her, displaying her as powerless compared to the women, both reflective of the view the morality police had of her, and their own powerful demeanor. As Marjane continues to beg (“Pity! Have pity!”), she is framed in a sea of black, until it is just Marjane against the dark backdrop, with a claw-like hand tightly gripping her shoulder. The music swells, creating an environment of anxiety. As the audience begins to fear the worst, the camera slowly pans back up to the women, the music fades away, and the women are suddenly disinterested. They walk away and Marjane is free. The film employs music and darkness to create anxiety in the audience and to better demonstrate the scare-tactics used by the morality police. By doing so, the film explains the environment of Iran at the time, in which even a small child could not express herself without being targeted.

Their all-black chadors create the illusion of overarching power, and as Marjane is begging to be let go, the view pans down to her, displaying her as powerless compared to the women, both reflective of the view the morality police had of her, and their own powerful demeanor. As Marjane continues to beg (“Pity! Have pity!”), she is framed in a sea of black, until it is just Marjane against the dark backdrop, with a claw-like hand tightly gripping her shoulder. The music swells, creating an environment of anxiety. As the audience begins to fear the worst, the camera slowly pans back up to the women, the music fades away, and the women are suddenly disinterested. They walk away and Marjane is free. The film employs music and darkness to create anxiety in the audience and to better demonstrate the scare-tactics used by the morality police. By doing so, the film explains the environment of Iran at the time, in which even a small child could not express herself without being targeted.

The film presents Westernization in Iran as both a distraction from the horrors of daily life and an act of rebellion. The Revolution brought with it an entirely new set of rules to follow, and people felt imprisoned in their own country. In this film, Satrapi presents Marjane as caught in the middle of a shift. She is witness to the changing times but still remembers freedom. As such, through Persepolis, the audience learns how “repressive regimes work over time on the individuals who are subject to them, leading citizens toward self-censorship and self-saving scapegoating of others” (Prasch 81). More importantly, we learn of the underground resistance to the repressive regime and the “tangle of Westernizing tendencies” (Prasch 81). Westernization in Iran acted as a form of rebellion, a set of small actions conducted by many individuals that require the morality police in the first place. Marjane’s small act of rebellion, buying a pirated CD and wearing clothes out of uniform, is used by Satrapi to subtly “critique the forces that work to suppress any manifestation…of cultural currency” (Tensuan 96) and demonstrate the extent of the restrictive regime at the time. While Marjane was set free, that was not the fate of many who were caught.

The film presents Westernization in Iran as both a distraction from the horrors of daily life and an act of rebellion. The Revolution brought with it an entirely new set of rules to follow, and people felt imprisoned in their own country. In this film, Satrapi presents Marjane as caught in the middle of a shift. She is witness to the changing times but still remembers freedom. As such, through Persepolis, the audience learns how “repressive regimes work over time on the individuals who are subject to them, leading citizens toward self-censorship and self-saving scapegoating of others” (Prasch 81). More importantly, we learn of the underground resistance to the repressive regime and the “tangle of Westernizing tendencies” (Prasch 81). Westernization in Iran acted as a form of rebellion, a set of small actions conducted by many individuals that require the morality police in the first place. Marjane’s small act of rebellion, buying a pirated CD and wearing clothes out of uniform, is used by Satrapi to subtly “critique the forces that work to suppress any manifestation…of cultural currency” (Tensuan 96) and demonstrate the extent of the restrictive regime at the time. While Marjane was set free, that was not the fate of many who were caught.

By expanding on the underground resistance present in Iran during and post-Revolution, the film explains that many people did not accept the new regime and were resistant against it. Through this, Persepolis paints the Iranian people in a new light, one in which citizens did not want to lose their home country and culture. Of course, while this film is not a non-fiction, it is based on a graphic novel written by Satrapi, who used her own life as the building blocks for the story. However, the fact that it has been deemed a piece of propaganda by Iran might underline some truthfulness in Satrapi’s storytelling. As Davis explains,

“Perhaps we should not simply intellectualize history, know it only as something that happened, but understand it as an experience – that of the historical actor, the historian, and the student…no history is definitive; it is simply part of a collective work in progress” (15).

By watching this film, audiences may begin to understand that the Iran post-Revolution, or even the Iran of modern day, is not reflective of the governmental attitudes present in the country. Rather, the Iranian people were (and are) being forced into compliance by a stronger government and their resistance puts them at risk.

Upon returning home, Marjane begins listening her new black market cassette tape of Iron Maiden. She dances exuberantly, with her recent scuffle with the morality police quickly forgotten. As she dances, the scene fades into a battleground with the song still playing in the background, adding a sense of urgency and disorientation. The ground is dark and uninviting, seemingly burned down and smoldering from bombs. Small silhouettes are seen scampering over the war-torn hills, running towards an unseen enemy. Focusing on the soldiers rather than the attackers is poignant in that it demonstrates the blind dedication the soldiers have to the Iranian Army, as they run at an unseen, but obviously much more powerful enemy.

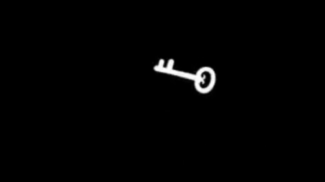

A voiceover is heard, urging the soldiers on, saying in a menacing, booming voice that by dying a martyr, their blood is injected into the veins of society. Meaning that martyrs help keep society alive, or at least keep the unjust regime alive. Slowly, all of the soldiers are gunned down save for one. As she runs over the last hill, a bomb explodes and she is disintegrated. The screen fades to black and a key is seen, thrown into the void. Suddenly, the audience realizes that the key harkens back to the key that the government was giving to the children, saying that if they died in war, the key would grant them access to heaven. Then, we realize that through indoctrination, the martyrs fighting on the battlefield were children who went to war because the government had brainwashed them. This particular moment explicates the unjust actions of the Iranian government. They were comfortable sending in untrained, young children as soldiers, to fight for a cause they did not understand.

A voiceover is heard, urging the soldiers on, saying in a menacing, booming voice that by dying a martyr, their blood is injected into the veins of society. Meaning that martyrs help keep society alive, or at least keep the unjust regime alive. Slowly, all of the soldiers are gunned down save for one. As she runs over the last hill, a bomb explodes and she is disintegrated. The screen fades to black and a key is seen, thrown into the void. Suddenly, the audience realizes that the key harkens back to the key that the government was giving to the children, saying that if they died in war, the key would grant them access to heaven. Then, we realize that through indoctrination, the martyrs fighting on the battlefield were children who went to war because the government had brainwashed them. This particular moment explicates the unjust actions of the Iranian government. They were comfortable sending in untrained, young children as soldiers, to fight for a cause they did not understand.

This scene brings the idea that even with the seeming mirage of limited free will, indoctrination is everywhere. Children are being forced to fight for a cause they do not understand, all for the sake of keeping the regime alive. Free will in Iran is a farce and it does not truly exist. Throughout the school scenes in the film, teachers ensure their students that the new regime is one that boasts freedom for its citizens, though we know that this is a lie. Not only are the women forced to wear a hijab, people are limited in their clothing, their music, and the way they act. Finally, even their lives are limited, as they are persuaded to fight for the country that cares little for their wellbeing, only for their ultimate success.

This scene brings the idea that even with the seeming mirage of limited free will, indoctrination is everywhere. Children are being forced to fight for a cause they do not understand, all for the sake of keeping the regime alive. Free will in Iran is a farce and it does not truly exist. Throughout the school scenes in the film, teachers ensure their students that the new regime is one that boasts freedom for its citizens, though we know that this is a lie. Not only are the women forced to wear a hijab, people are limited in their clothing, their music, and the way they act. Finally, even their lives are limited, as they are persuaded to fight for the country that cares little for their wellbeing, only for their ultimate success.

This scene harkens back to Paths of Glory, where General Mireau forces his regiment to fight in a battle knowing that the possibility of success would be low, just to be considered for a promotion and another star. For the sake of personal gain, General Mireau sends his soldiers to fight and many of them die going into the battlefield. He forces Colonel Dax to give the orders and send his men to die, blinded by his goal of a promotion. Similarly, in Persepolis, the Islamic regime sends children into the battlefield, knowing that they will die against the bombs and bullets of the opposing side. This was all to reinforce their own Islamic ideals and values, and resist against the opposing side. In both of these films, the soldiers have no free will and are shamed for not risking their lives. Both films serve as anti-war films, criticizing the powers at play and political ideologies during war.

Persepolis is a landmark film in that it presents Revolution-era Iran in a different light than most films. It explains the “transition period”, or the time between the downfall of the Shah and the eventual acceptance of the new regime. Oftentimes, this transition is forgotten, as historians skip over the resistance and go from the Shah’s regime to the Ayatollah’s, however, the transition is an incredibly important section of Iranian history. The Iranian Revolution is generally presented through the lens of politics, going behind political reasoning and motivation. This film, however, offers a different aspect of the Revolution, one shown from a child’s view, her struggles with learning new history, new prayers, and new practices. So we learn of Marjane’s life as a child, and we see what happens during and after the Revolution. We understand “how the imposition of the veil was experienced by someone resistant to it” (Prasch 81). We see her rebellion and the rebellion of others, and we see her exile, return, and eventual move to Paris. After she returns from abroad, she realizes the new Iran is unlike the one from her childhood. The Islamic regime has changed everything, and has left very few reminders of the city she grew up. As an audience, we are meant to see the film and understand how a revolution and a war can change a country, how many lives it stole, and how many lives were forever changed. We are meant to feel the heartbreak that Marjane feels, suddenly dropped into an environment she once knew, only to be greeted with an alien world. All of these are meant to shed light on the Revolution and make it more understandable for people who have little knowledge of this time period, but doing so in a way that is also more relatable for the audience. The film audaciously elucidates Iran pre and post-Revolution to paint a more complete picture of the Revolution and its effects on the citizens of Iran, rather than a government-centric description, leading to a more transparent representation of the war-torn country.

References

Davis, Jack E. “New Left, Revisionist, In-Your-Face History: Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July Experience.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies, vol. 28 no. 3-4, 1998, pp. 6-17.

Nabizadeh, G. “Vision and Precarity in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 44 no. 1, 2016, pp. 152-167.

Prasch, T. “Persepolis (2007) (review).” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies, vol. 38 no. 2, 2008, pp. 80-82.

Tensuan, T. M. “Comic Visions and Revisions in the work of Lynda Barry and Marjane Satrapi.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 52 no. 4, 2006, pp. 947-964.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Uncovering Iran: Revolution and Rebellion An analysis on Iranian life during and post-Revolution, through the film Persepolis,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 02.24.18 / 3pm

- Category:

- Academic Papers, Films

4 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?]