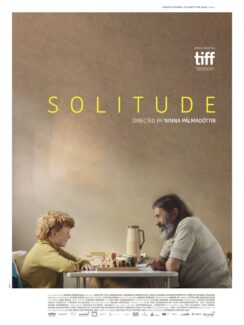

Solitude (Ninna Pálmadóttir, 2023): Iceland | Slovakia

Reviewed by Elyssa Crutchfield. Viewed at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival 2024.

Everybody has to find their place in the world, but who says there’s any “right” time to do so? The unusual story of friendship across generations, Solitude (2023), is an Icelandic, French, and Slovakian-produced film directed by Ninna Pálmadóttir. Rúnar Rúnarsson’s screenplay encompassed common themes and characters explored by Pálmadóttir in the past and instantly caught her attention when she read it. Paperboy, the winner of the 2020 Edda Award for best short film, is about a young boy who delivers newspapers, and Old Dogs Die is about a solitary farmer. Pálmadóttir received an MFA in film from NYU Tisch and has worked on numerous productions, but as an Icelandic filmmaker, Solitude apparently resonated with her, allowing her to bring the two characters and their relationship to life.

Everybody has to find their place in the world, but who says there’s any “right” time to do so? The unusual story of friendship across generations, Solitude (2023), is an Icelandic, French, and Slovakian-produced film directed by Ninna Pálmadóttir. Rúnar Rúnarsson’s screenplay encompassed common themes and characters explored by Pálmadóttir in the past and instantly caught her attention when she read it. Paperboy, the winner of the 2020 Edda Award for best short film, is about a young boy who delivers newspapers, and Old Dogs Die is about a solitary farmer. Pálmadóttir received an MFA in film from NYU Tisch and has worked on numerous productions, but as an Icelandic filmmaker, Solitude apparently resonated with her, allowing her to bring the two characters and their relationship to life.

When Gunnar, who has up until this point lived comfortably alone on his vast farmlands in northern Iceland, inherited from his father and his father before him, is forced to move due to the advancing water from a hydroelectric dam, he moves into a suburban part of Reykjavík. His land is repossessed by the government, and he receives a generous 150 million krónur, or just over a million USD, from the government, which he uses to purchase a small, family-sized home. In Reykjavík, he largely keeps to himself, taking daily excursions around the city, collecting cans and trash, and observing the busy urban world around him from a distance. It isn’t until Ari, a 10-year-old paperboy who lives across the street, greets him on a walk, and newspapers subsequently start being left at his door despite Gunnar’s protests, that he begins to form a meaningful connection. When Ari turns up on his doorstep, locked out of his house, and looking for someone to kill a few hours with, a friendship between the two very different characters starts to develop.

Solitude is a coming-of-age story, not only of Ari but of Gunnar, as he re-emerges into contemporary society and discovers how he fits into a world that changed without him. Their relationship, the cross-generational friendship, is the driving force behind Gunnar’s change, his willingness to emerge from his shell, from his solitude. There is minimal dialogue between the two characters; often their interactions are silent, driven by body language and eye contact, which change over time, showing their growing comfort with one another. Ari is caught between his divorced parents struggling to co-parent and finds solace in his friendship with his reclusive neighbor. He compels Gunnar to get a television; they play chess, eat frozen pizza, and dance together in Gunnar’s kitchen to his radio.

Solitude is a coming-of-age story, not only of Ari but of Gunnar, as he re-emerges into contemporary society and discovers how he fits into a world that changed without him. Their relationship, the cross-generational friendship, is the driving force behind Gunnar’s change, his willingness to emerge from his shell, from his solitude. There is minimal dialogue between the two characters; often their interactions are silent, driven by body language and eye contact, which change over time, showing their growing comfort with one another. Ari is caught between his divorced parents struggling to co-parent and finds solace in his friendship with his reclusive neighbor. He compels Gunnar to get a television; they play chess, eat frozen pizza, and dance together in Gunnar’s kitchen to his radio.

Both characters are in their own ways naive to the world around them, Gunnar aimlessly wandering through Reykjavík with no desire to work or need for money and no community he is drawn to. The cinematography of the film is powerful, and the brilliant wide shots of the Icelandic landscapes are contrasted to the tight, isolating shots of Gunnar in the city. He is often in confined spaces such as a bus or narrow alleys, and even in larger spaces such as the park, he finds himself sitting in a narrow enclave that allows the camera to enclose him in his own reservations. There are exceptions to these, and they are significant. For example, when Gunnar witnesses a protest regarding an Afghan refugee being denied asylum and deported, and when he attends Ari’s football game in place of his absent parents, the focus of the shots is not Gunnar, but instead Gunnar in a larger group, a member of society. The passive resignation he displays is replaced with a genuine investment in the people around him.

There is a lingering uncertainty as to whether or not Gunnar will be able to successfully acclimate to urban life even when the film ends, but Gunnar’s willingness to branch out, even to a limited extent, is indicative that he will continue to try. He lets go of his reservations, of his home, of his only friend there, a beautiful white horse he keeps a framed photo of, but he doesn’t metamorphosize into a completely different person in the process. I think that even if the set-up for the story may be cliche and the ending fails to satisfy audience members’s desire for closure, whether that be emotional or regarding the direct plot itself, the story rings very true because of the intimacy of its characters and their connection to the real world, and that this film is worth watching.

There is a lingering uncertainty as to whether or not Gunnar will be able to successfully acclimate to urban life even when the film ends, but Gunnar’s willingness to branch out, even to a limited extent, is indicative that he will continue to try. He lets go of his reservations, of his home, of his only friend there, a beautiful white horse he keeps a framed photo of, but he doesn’t metamorphosize into a completely different person in the process. I think that even if the set-up for the story may be cliche and the ending fails to satisfy audience members’s desire for closure, whether that be emotional or regarding the direct plot itself, the story rings very true because of the intimacy of its characters and their connection to the real world, and that this film is worth watching.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Solitude (Ninna Pálmadóttir, 2023): Iceland | Slovakia,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 03.03.24 / 11pm

- Category:

- Films, Santa Barbara Film Festival 2024

24 Comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?]