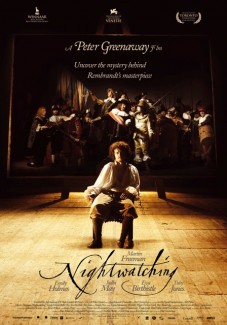

Nightwatching (Peter Greenaway, 2007): Netherlands

Reviewed by Colin Marshall. Viewed on DVD.

The first frame of Nightwatching‘s striking chiaroscuro cinematography signals a film about and infused by the spirit of Rembrandt van Rijn. That we need not wait five minutes for the first doughy male nude — here, the Dutch master himself — to tumble into the obsessively theatrical setting signals a film by, and infused with the sensibility of, Peter Greenaway. His first release of the decade outside the baroque multimedia Tulse Luper’s Suitcases project, the movie, an eerily gleaming surface of hyper-articulate dialogue, 17th-century accoutrements and obscurantist vulgarity, would seem to mark a return to the Greenaway style of yore.

The first frame of Nightwatching‘s striking chiaroscuro cinematography signals a film about and infused by the spirit of Rembrandt van Rijn. That we need not wait five minutes for the first doughy male nude — here, the Dutch master himself — to tumble into the obsessively theatrical setting signals a film by, and infused with the sensibility of, Peter Greenaway. His first release of the decade outside the baroque multimedia Tulse Luper’s Suitcases project, the movie, an eerily gleaming surface of hyper-articulate dialogue, 17th-century accoutrements and obscurantist vulgarity, would seem to mark a return to the Greenaway style of yore.

You may know this style for its having produced 1982’s The Draughtsman’s Contract, of which some of Greenaway’s followers have ever since bemoaned the lack of a precise duplicate. Not that Nightwatching bears many of the older picture’s qualities: gone are the anachronistic mobile phones and pop-art wall hangings; gone is composer Michael Nyman, a single (though admittedly appropriate) string piece repeated ad nauseam expanding to fill most of his acclaimed score’s stead. But the statues portrayed by live human actors remain. In fact, they’ve multiplied, eventually lining the background of an entire tail-end party scene.

This relative reining-in of Greenaway’s vaunted avant-garde impulses may come as a nod to the story’s roots in historical facts: specifically, the facts of Rembrandt’s life, and more specifically still, the circumstances of the creation of his best-known canvas, the enormous Night Watch, in 1642. The tale, as Greenaway tells it, has a reluctant Rembrandt considering a commission from Amsterdam Militia Captain Frans Banning Cocq to paint a portrait of he and his comrades in arms. Pressured by his wife to take the money and bear it, he finds the Militia, during his preparation, to be a veritable overturned log of slimy power struggles and ugly microfeuds. When one of its men falls victim to friendly musket fire, Rembrandt suspects murder, availing himself of his only forum to air his accusation: the painting itself.

Sound as this may like an art history lecture delivered by Oliver Stone, the presiding mindset is less paranoid than speculatively scholarly, and aggressively so. The substantiatable history undergirding the drama comes to a fairly thin gruel, to be sure, but as kookiness goes, this all keeps a safe distance from, say, second gunmen and living Elvises. Besides, it would take a bold defender indeed to number pure veracity as one of Greenaway’s strengths, or even as one of his interests. Here, he’s clearly into Night Watch to the extent that the stories surrounding it build the framework for a character study. (He saves the study of the painting itself for the associated documentary Rembrandt’s J’Accuse, which occupies the two-DVD package’s second disc.)

And what a character, this Rembrandt. One is tempted to call Greenaway’s selection of young Martin Freeman an act of stunt casting, given how strongly the actor has come to be identified with a certain stripe of the wearily wisecracking modern damned. His past roles include the agency-stripped Arthur Dent, “protagonist” of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and despondent 30-year-old paper salesman Tim Canterbury of The Office. Neither character suggests Freeman’s aptitude for portraying the lusty Dutchman, a displaced hackle-raiser bumped from his low social class by dint of his astounding skill with a brush. Fortunately, their subject about 300 years outside living memory, Greenaway and Freeman are free to create their own Rembrandt. The result is a figure who lacks the outward (and outward-only) refinement of Greenaway’s most memorable leads but compensates with sincerity, sheer generalized ardor and a whole lot of cursing.

Jutting outward at dozens of odd angles, the film in which he finds himself could hardly be called a standard biopic. It’s not a piece of theater, though with its often spare, expressionistic settings, it’s not exactly a regulation-lush period piece either. It’s not an art history lecture, though nor is it not an art history lecture. Perhaps it’s best described as series of intellectual and aesthetic Greenaway riffs on subjects surrounding the man, his place, his work of art and his women. Emphasis, by the way, on the latter: Rembrandt’s three loves of the period — the arranged but surprisingly suitable Saskia van Uylenburg; the bottom-caste Geertje Dircx, possessed of almost negative amounts refinement or inhibition; and the demure, youthful, barely-featured servant Hendrickje Stoffels — each come introduced, chapter-like, with a fourth-wall-breaking monologue from the artist. (“This is me with Saskia…”, “This is me with Geertje…”, “This is me with Hendrickje…”)

Such a flourish, to Greenaway’s detractors, no doubt emblematizes what they consider to be the director’s flamboyant indiscipline, and maybe it does, but those looking for the absolute finest in flamboyant indiscipline need search no further than the Greenaway oeuvre. Despite — maybe because of — its excesses and confusions, this film is something, and it doesn’t go down with tasteless smoothness, nor does it fade from memory immediately upon digestion. Never will Nightwatching be mistaken for the product of a Robert McKee workshop. Admittedly, with seven years passed since his brilliant (and unfairly sneered-at) Fellini homage 8½ Women, Greenaway seems a touch rusty, but he still, as a long-standing member of the “if you want a story, read a storybook” camp, understands the power of film better than do most working directors. Here is a chapter, if not a major one, in his ongoing j’accuse against cinematic uncreativity.

DVD extras: short cast and director interviews, second disc with documentary Rembrandt’s J’Accuse.

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]