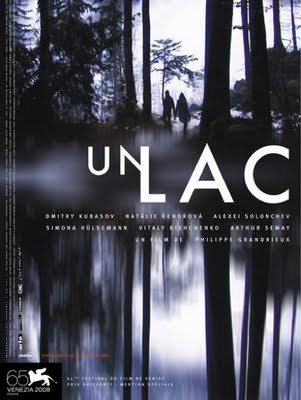

Un Lac (Philippe Grandrieux, 2008): France

Reviewed by Guy Dolev. Viewed at the Mann Chinese Theater 6, AFI Film Festival 2009, Hollywood, California.

After more than five years, avant-garde French filmmaker, Philippe Grandrieux, enters the film festival 2009 circuit with his latest work, Un Lac (A Lake), a dizzying, visual poem photographed by the director himself in the Swiss Alps. Using no more than six characters and straying far from the established notions of cinematography and narrative in film, the piece feels like something between an experimental video-art installation and one of Ingmar Bergman’s bleak feature films, though the work itself has perhaps no conceivable outside influence. Truly, the film saw many of the theater’s patrons walk-out as it offers nothing for the average “moviegoer” audience, yet those with wrinkled foreheads and raised eyebrows were likely left the house with shards of the film’s understated agony in their cinematic skin.

After more than five years, avant-garde French filmmaker, Philippe Grandrieux, enters the film festival 2009 circuit with his latest work, Un Lac (A Lake), a dizzying, visual poem photographed by the director himself in the Swiss Alps. Using no more than six characters and straying far from the established notions of cinematography and narrative in film, the piece feels like something between an experimental video-art installation and one of Ingmar Bergman’s bleak feature films, though the work itself has perhaps no conceivable outside influence. Truly, the film saw many of the theater’s patrons walk-out as it offers nothing for the average “moviegoer” audience, yet those with wrinkled foreheads and raised eyebrows were likely left the house with shards of the film’s understated agony in their cinematic skin.

The film examines -without using more than maybe 20 lines of dialogue- a family living in the desolation of the frozen winter of the Alps, in which an epileptic brother who works as a logger and his sister who are both coming of age act upon their desire to embrace each other; however, this clearly can’t last and when another young man comes to the eternal cold in search of work, the union between the siblings will be changed forever. We see the nature of a family disrupted as a direct result of the newcomer, as if the director is suggesting that the isolation this family has isn’t a curse set upon their lot, but a sort of blessing.

Silence and intensity pervade the white mountains and black, scintillating lake, shot in color, yet naturally very black and white, giving the sense of bitter cold and stark desperation. Focusing his hand-held, shaking camera on the faces of his leading actors (Dmitry Kubasov as Alexi and Natalie Rehorova as his sister Hege, as well as a few other Russian actors and actresses), the cinematography itself seems to accentuate and imitate Alexi’s epileptic fits. At other times, such as the startling dinner “scene” in which the table is never properly framed by the camera, we see instances of different characters’ faces in close-up, which lends paranoid feelings of uncertainty as to who else might be at the table, since we only see individual faces; significantly, we aren’t brought closer to the characters we are familiar with, though we get a better understanding of their psychological makeup.

While the film is obviously much different from the average “movie,” Un Lac, though it might not be at all enjoyable for most audiences, holds a power to it that ordinary film over the years has unintentionally desensitized audiences to. Undoubtedly, the photography is unique and beautiful, as is the minimal storyline and the unconventionally organized structure in which it’s told. The viewer will leave the cinema -hopefully not before the film has ended- feeling that something in the film has left them without closure or perhaps even disturbed by the loneliness of the family and the bleak, but certainly very beautiful depiction of life existing in places where life is rarely found. In any case, the film is extremely significant for its contribution to cinema in its response to the age-old question: what is it?

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Un Lac (Philippe Grandrieux, 2008): France,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 11.04.09 / 12pm

- Category:

- AFI Filmfest 2009, Films

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]