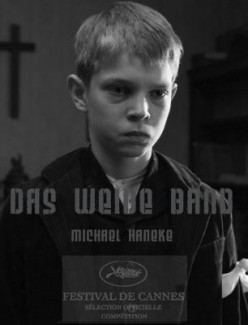

Das Weisse Band / The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, 2009): Austria/France/Germany/Italy

Reviewed by Guy Dolev. Viewed at Mann Chinese Theater 1, AFI Film Festival 2009, Hollywood, California.

Austrian auteur Michael Haneke wins the immensely prestigious Palme d’Or award at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival with his period drama, Das Weisse Band (the White Ribbon). Set in the early 20th century before the outbreak of World War I in a small German village, the town’s people begin to observe violent acts that occur unaccountably against prominent members of the community and a wealthy baron’s family whom most of the citizens rely upon for their employment.

Solemnly narrated by the young schoolteacher long after the events in the film have taken place and shot in an austere black and white format, the film takes on a severity reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s cinema. The narrator’s words immediately tell that there is some doubt as to the nature of the account, as he claims not all of it he knows from personal experience, but some he became aware of through hearsay. The director has expressed a passion for filming historical work in black and white as he tends to visualize it as such. Brilliant cinematography surrounds the work such as a landscape shot of the workers in the wheat field and the church scenes with its children’s choir. Using faces that match what the director feels are old-fashioned faces, he went through an arduous process of casting for the film, searching small Romania and Northern German villages for the right “weather-beaten” faces he was looking for.

Beginning with a trap set for a doctor, who rides home and becomes injured as his horse trips on an invisible wire tied between the posts of his home which he rides through daily, a picture of unsettling cruelty paints itself before our eyes. Strangely enough, the wire is removed before a proper investigation can be conducted. The action intensifies when a priest, and father, comes to learn of his children participating in bedlam in the schoolhouse, for which he punished them by forcing them to wear white ribbons, symbolizing innocence. Rather than teach the children about their maturing sexuality, the priest has his son’s hands restricted with rope during the night so he won’t be able to touch himself. After the baron’s barn is burned and his son is beaten, the village is held accountable, particularly a peasant family whose mother was killed accidentally while working in a factory owned by the baron. Understanding this to be a form of revenge, the baron dismisses a girl from this same family who was working as his children’s caretaker, fearing that she may be in a position to cause him harm.

This is a striking tale of morality, showing the cruelty of mankind and the severe disciple associated with being German, as seen in the neat and proper appearance of every aspect of the adult life in the film. At every turn of hostility, the kidnapping, the beating, the children seem to be entirely too close to the action, but surely they are too young and naive to have any involvement with these events…

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Das Weisse Band / The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, 2009): Austria/France/Germany/Italy,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 11.09.09 / 6pm

- Category:

- AFI Filmfest 2009, Films

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]