Power in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (Stanley Kubrick, 1971): UK | USA

Paper by Josh Solomon.

Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) is based on the controversial novel, A Clockwork Orange, written by Anthony Burgess. The title of the film is a reference to the Cockney expression “As queer as a clockwork orange,” meaning that something is odd, strange or unusual, but appears normal on the surface.1 The film is exactly this. Kubrick depicts the future as a horrifying dystopia in which chaos is the primary force and people lack individuality and appear machine-like. The film is filled with metaphors instilled in imagery and script along with many other ideological views regarding politics and human nature. Alex, our “humble” (Alex ironically refers to himself as humble in voice-over narrations throughout the movie) antihero, is a juvenile with a black hole for a heart; his principal interests include rape, violence and Beethoven.2 Kubrick depicts Alex as the personification of evil, yet Alex is a very appealing and charismatic character. During the night Alex and his droogs (droogs is Nadsat for gang of friends, Nadsat is a language specifically created by Burgess for A Clockwork Orange that is a mixture of Russian and English) take part in their favorite sadistic rituals and psychedelic drugs. Like all protagonists, Alex has a goal; his objective is to become as powerful as possible, thus A Clockwork Orange is a satirical science fiction film about power. Kubrick expresses his views about many forms of power ranging from individual power, exemplified by Alex, through social and governmental power. Kubrick expresses his distrust of authoritarian governments, especially when they suppress individual rights. The years prior to the release of A Clockwork Orange (1960-1971) were extremely influential to the film and the messages the film contains.

Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) is based on the controversial novel, A Clockwork Orange, written by Anthony Burgess. The title of the film is a reference to the Cockney expression “As queer as a clockwork orange,” meaning that something is odd, strange or unusual, but appears normal on the surface.1 The film is exactly this. Kubrick depicts the future as a horrifying dystopia in which chaos is the primary force and people lack individuality and appear machine-like. The film is filled with metaphors instilled in imagery and script along with many other ideological views regarding politics and human nature. Alex, our “humble” (Alex ironically refers to himself as humble in voice-over narrations throughout the movie) antihero, is a juvenile with a black hole for a heart; his principal interests include rape, violence and Beethoven.2 Kubrick depicts Alex as the personification of evil, yet Alex is a very appealing and charismatic character. During the night Alex and his droogs (droogs is Nadsat for gang of friends, Nadsat is a language specifically created by Burgess for A Clockwork Orange that is a mixture of Russian and English) take part in their favorite sadistic rituals and psychedelic drugs. Like all protagonists, Alex has a goal; his objective is to become as powerful as possible, thus A Clockwork Orange is a satirical science fiction film about power. Kubrick expresses his views about many forms of power ranging from individual power, exemplified by Alex, through social and governmental power. Kubrick expresses his distrust of authoritarian governments, especially when they suppress individual rights. The years prior to the release of A Clockwork Orange (1960-1971) were extremely influential to the film and the messages the film contains.

An audience normally would not empathize with a character such as Alex, but Kubrick manipulates the audience into doing so. Alex’s heinous tendencies are justified by means of his personality and by the society he lives in. Alex is a handsome youth who appears to be a product of his dreary society. He is smart, clever and aware of his world, unlike the other characters who submit to the society and do not attempt to rebel against it. By using unattractive, bland, stupid, or arrogant people who are obstacles (or victims) to Alex, the audience does not feel as horrified by Alex’s sadistic acts. For example, the rich in this film live on the outskirts of town and so do not have to live with its faults and ugliness. The wealthy are either portrayed as manipulative politicians (the writer) or arrogant bimbos (the cat-lady). By dehumanizing and making these acts of violence almost comical, Kubrick allows the audience to become concerned with the ideology of the film, to look at the symmetry of narrative and the contradictions of Alex’s character.3

Throughout the movie, Alex, almost poking fun at the audience for being compassionate with, and manipulated by him, refers to himself (numerous times) as “your [the audiences] humble narrator.” Alex’s persona is based on, or in reference to King Alexander the III of Macedon (Alexander the Great) who was an accomplished conqueror and known for a particularly bloody battle in which no lives were spared, including those of women or children. Kingly power is virtually the same as individual power in that one takes what they want, but on a larger scale. Additionally, King Alexander’s life is almost parallel to Alex’s, Alexander was renowned and celebrated, then exiled for his irresponsible actions and after much hardship came back from exile to become king. While our “little” Alex is free, he then falls when he loses his free will and is then resurrected as his violent, old self.

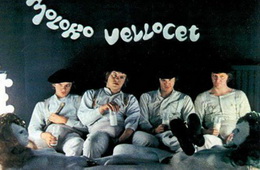

In order to exert control over the audience, Kubrick gives Alex the power of omniscient voice-over narration and by doing so, the audience’s only perception and view into this world is controlled by Alex. In the opening scene of the movie we are introduced to Alex with his droogs in the Korova milk bar drinking “milk” that is laced with psychedelic drugs. The opening shot is a tracking shot that begins with an eye-line match, close-up of Alex and tracks backwards to show Alex and his droogs at the back of the bar in a medium shot (another eye-line match). We instantly identify with Alex, because while his droogs are in the midst of a psychedelic trip and do not appear to be conscious, Alex is more than conscious, he is thinking and we hear his thoughts through voice-over narration. Alex is the only one with his feet on a table, a classic dominant male position that also suggests being comfortable with someone or in someone’s home. By having his feet on the table, Alex is inviting the audience into the story almost as if to say “gather around children and you will hear the story of the great Alex De’Large.” The camera maintains Alex as the primary object of the shots while tracking backwards to reveal the whole bar. This establishes the dominant type of shot in the movie that has Alex as the primary object of the frame. However, Alex only maintains his control of the frame until he undergoes the Ludivico treatment. Kubrick makes the camera sympathetic with Alex, camera angles are motivated by what is going on in the scene in order to give the audience the same sensation Alex is feeling. For example, during the Ludovico treatment, the audience (like Alex), cannot take their eyes off of the videos and as we watch while Alex vividly describes his horrific experience. Periodically, Kubrick cuts back to a wide angle, extreme close-up of Alex’s face, which is stricken with grotesque horror and pain. Alex’s distorted facial expressions are grotesque to the point where the audience feels the same nausea Alex describes, however the audience is reacting to Alex instead of the short films. The audience feels intimate with Alex which causes them to feel resentful when he is stifled by authority.4 Later in the film, when Mr. Alexander, the politician and writer, is torturing a post-Ludovico Alex with Beethoven’s 9th symphony, Alex attempts suicide by jumping out of a second story window. The audience experiences this act of suicide through the emotional narration of a tortured Alex. When Alex jumps, Kubrick cuts to a point of view shot of him committing suicide. By shooting from Alex’s point of view, the views of Alex’s victims and oppressors become subjective while Alex is able to assert narrative control by making his victims and oppressors appear more heinous.

In order to force the audience to think about the ideology of the film, Kubrick uses metaphorical imagery. For example, each scene Kubrick creates reflects the personality of the character with which it is associated. When Alex breaks into the old cat women’s home, her house is filled with obscene pictures of naked women posed in sexual positions but are lesbian-oriented, such as a woman licking another woman’s breast. Kubrick deliberately uses symbolic props to trigger a thoughtful response from the audience. During the take when Alex and the cat women are fighting, Alex holds a large white sculpture of penis as a weapon while the women swings at Alex with a sculpture of Beethoven. When Alex smashes the women’s face with the phallus, Kubrick creates a visual metaphor or montage by juxtaposing the women’s head with a painting of a mouth within another mouth and then an image of a woman’s genitals.

Classical music is generally regarded as emotionally provocative, moving and powerful. Kubrick uses classical music in the mise-en-scene of A Clockwork Orange to serve as a motif that lessens the brutality but also serves as an ironic counterpoint. Classical music is viewed as a benevolent form of music that only the most sophisticated and intellectually proficient can understand and appreciate. Alex is extremely passionate about classical music, in particular Beethoven, and is actually inspired by it to commit acts of violence. For example, during the scene in which Alex and his droogs are walking along a river, Alex hears a spurt of Beethoven and is inspired to kick Dim and Georgie into the river and cut Dim with a knife. Additionally, classical music acts as a drug for Alex, every time he listens (before the Ludivico treatment) he is moved into a state of ecstasy or as he calls it “pure bliss” and has visions of or commits acts of ultra-violence.

A Clockwork Orange is a social and political satire of post-World War II England. The questions that the film investigates were triggered by the issues confronting England. During this time period, due to economic depression, many of the English were out of work causing political power struggles and social unrest. With so many people out of work, the government was required to build affordable housing which looked identical to the building Alex lived in (because it was). This large scale unrest led to a lawless and chaotic society. Workers were on strike for weeks at a time, there were rolling electrical blackouts for days on end, a rise in working class violence and because of this chaos the youth were ignored. When law and order break down people tend to form packs for protection, which in England’s case led to juvenile gangs. England’s government needed to find a solution to this lawless society, one solution was to exert the government’s power over the people. This manifested itself in many ways, one being new psychiatric treatments similar to the Ludivico technique. The world of the film is not in fact so different from the 1960’s and 1970’s England.

Kubrick created this film in order to explore and satirize the current issues of England. One of the major aspects Kubrick explores is the reaction of society to an unstable and lawless culture. When chaos breaks free, humans find themselves desiring security and comfort so they tend to group together in gangs. This is especially true with male teenagers. In the film Alex and his gang of droogs feed off of each other for social confidence, strength, and protection. The droogs represent a classic mob; they are mindless followers of Alex (until Alex over-exercises his authority) and they feed on each other for power. Kubrick accurately portrays how men in packs will tend toward mob mentality and how they take part in hetero-social violence such as rape and the use of women as mere objects.

Power is discussed and defined in many ways throughout the movie, but the most basic form of power it explores is individual power. This is the form of power Alex pursues and the audience best understands. A motif that exemplifies this form of power is the phallus which represents gender-based power and authority. For example, Alex and his droogs wear futuristic all-white uniforms with combat boots and codpieces that flaunt their sexuality and gender-based power. The codpiece personifies the droogs’ sadistic and sexual mentality. In addition to the cod-piece, Alex and the droogs wear clown masks to hide their identities; Alex’s mask has an extremely long and cylindrical nose (a phallus) that clearly shows that he is the alpha male of the group. Alex’s individual power derives from his physical presence, his ability to use it as intimidation or destruction and his free will.5 Kubrick defines individual power when Alex’s droogs confront him on his overly controlling and harsh leadership. When confronted, Alex asserts (to his droogs) “Have you not have everything you need? If you need a motor car, you pluck it from the trees. If you need pretty Polly, you take it.” Kubrick defines individual power as the ability to take or do what one wants, however, as happened to Alex due to his leadership methods, the best way to lose this power is to over-exercise or abuse it. Kubrick may be using Alex as a symbol of a dictator and his droogs as his public. Kubrick is making a direct statement about totalitarian governments by showing that when a leader (Alex) over-uses or exploits their power over their subjects they are destined to lose their control over them. At this point in the film Alex has lost total control of his droogs, to make matters worse he attacks Dim and Georgie (his fellow droogs) in an attempt to show his dominance. Alex continuously abuses his individual power by taking part in sadistic acts and thus causes the government to take his individual power away.

Individual power is a function of free will because one’s power derives from the ability to make choices. After being arrested and imprisoned, Alex loses his ability to exercise his individual power. He soon discovers the Ludivico treatment; a program that once completed would entail Alex’s release from prison. After undergoing the treatment, Alex loses his ability to take part in sadistic acts. He is unable to do so because the treatment causes him to have a painful physiological response to actions or thoughts of violence and sex. This eliminates Alex’s free will, which thus inhibits his ability to exercise his individual power. Prior to the treatment, Alex befriends the prison chaplain who argues (after the treatment is finished) that “The boy [Alex] has no real choice at all!…He ceases also to be a creature capable of moral choice!” Alex is still compelled toward sadism, but due to the fear of pain, can no longer take part in it. Alex has been turned into a clockwork orange.6 We (the audience) resent Alex being stifled by authority because we have developed an intimate relationship with him and we understand that it is morally righteous to have the choice between good and evil and choose evil rather than to become a mindless zombie of society.7

Kubrick explores the dangers of a state adopting violence, such as the Ludivico technique, as a means of control. The government in the film will deploy any means necessary to keep strict control over the individual in order to maintain law and social order. In order to maintain total control, the government dehumanized society by turning the individual into a mindless drone. Authoritarian governments are motivated to exert this control in order to achieve their political goals. Although we are never introduced to the inner workings of the corrupt government, Kubrick leads us to understand that it is an immoral institution. He creates a society in which we are instantly introduced to a dilapidated city that appears similar to communist Russia and people we meet are obvious products of that society. For example, Alex’s father and mother care more about going to their factory jobs than personally dealing with their son’s defiant behavior. The parents have been shaped and manipulated by this government so that work is more valued (to the country) than good parenting.Kubrick makes us condemn this government in the same way we would condemn Alex for his thuggish behavior.

The two government entities we are introduced to are embodied by the prime minister and Mr. Alexander, the leftist writer. The prime minister represents the conservative major political authority that attempts to suppress and manipulate the individual. The writer, ironically, is an advocate of individual power. Both politicians attempt to manipulate and use Alex as a means to achieve their goals, the acquisition of more power. Ironically, the writer wants to use (which will help) Alex to discredit the current regime and gain some form of political power. The prime minister on the other hand, originally wanted to enact a new reform that legally allowed the government to brainwash criminals. After the writer discovers that Alex is the murderer and rapist of his wife, he tortures and drives Alex to an attempted suicide. Once in the hospital, the prime minister comes to visit and bribe Alex in an attempt to restore the shattered public support for the government. While talking to Alex, the prime minister states that they (the government) imprisoned the writer in “an attempt” to keep Alex safe, however the liberal writer actually posed a political threat to the conservative government and they were able to use Alex as a pretext to lock up their political enemies. Kubrick is showing his distrust for the motivation and actions of maintaining power, and is questioning the extent to which government power should be exercised.

Stanley Kubrick created A Clockwork Orange in order to explore and discuss power in the mid-twentieth century. Kubrick created a highly saturated mise-en-scene that allows the audience to distance themselves from the violence taking place on screen and instead, look upon the important political and ideological issues, such as the abuse of government power. Kubrick uses many ingenious devices to manipulate his audience, the most prominent being the narrative authority of Alex’s voice-over narration, the other being the use of both diegetic and non-diegetic sound tracks of classical music (aside from “Singing in the Rain”). The film depicts the dangers of an authoritarian government abusing its power and suppressing the free will and power of the individual.

1. See Wikipedia ‘as queer as a clockwork orange’

2. Synopsis for A Clockwork Orange (1971): Internet Movie Data Base

3. Idea triggered by Stuart Y. McDougal’s book Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, chapter on narrative authority

4. Stanley Kubrick Directs, rephrase of idea from introductory chapter

5. Stuart Y. McDougal Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, idea from chapter on narrative authority.

6. Idea from chapter on A Clockwork Orange from Stanley Kubrick Directs pg 42-43

7. Cinema of Stanley Kubrick rephrased quote from Kubrick pg 182-183

Bibliography

Kubrick, Stanley J, A Clockwork Orange, Warner Brothers, 1971. Film.

Walker, Alexander, ed. Stanley Kubrick Directs. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, inc. 1971. Print.

Kagan, Norman, ed, The Cinema of Stanley Kubrick, Canada: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1972. Print

Phillips, Gene D, ed, Stanley Kubrick Interviews, Missisipi: University of Missisipi, 2001. Print.

Denby, David, ed, Members of the National Society of Film Critics Write on Film 71-72, New York: Simon and Schluster, 1972. Print.

McDougal, Stuart Y, ed, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2003. Print.

Ciment, Michael. Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange. 11/20/09

“1960’s”. Wikipedia. 11/18/09

Tezer, Adnan. Movie Analysis: A Clockwork Orange. Helium. 11/18/09

Ager, Rob. “A Clockwork Orange Analysis/Review”. collective learning. 11/21/09

Dirks, Tim. “A Clockwork Orange(1971)”. AMC Film Site. 11/18/09

Cohen, Alexander J.. “A Clockwork Orange and the Aetheticization of Violence”. University of Berkley California. 11/21/09

“A Clockwork Orange”. Spark Notes. 11/15/09

“Queer as a Clockwork Orange”. Wikipedia. 11/11/09

“A Clockwork Orange”. Internet Movie Data Base. 11/13/09

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Power in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (Stanley Kubrick, 1971): UK | USA,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 12.08.09 / 8pm

- Category:

- Academic Papers, Films

1 Comment

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]