One Thousand Year Song of Baobab (Motohashi, 2009): Japan

Reviewed by Nitsa Pomerleau. Viewed at the Santa Barbara Film Festival 2010.

I went to see One Thousand Year Song of Baobab (Baobabu No Kioku) on two motivations: I loved the poetics of the title and held a sort of delusional hope that the film would reference Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s book Le Petit Prince. To my cinematic happiness, this slow and sensitive observation of Senegalese village-life sheds the call-to-action tone common to documentaries and instead openly admires and mourns the baobab, summoning a poetic and very Little Prince-like relationship to the planet.

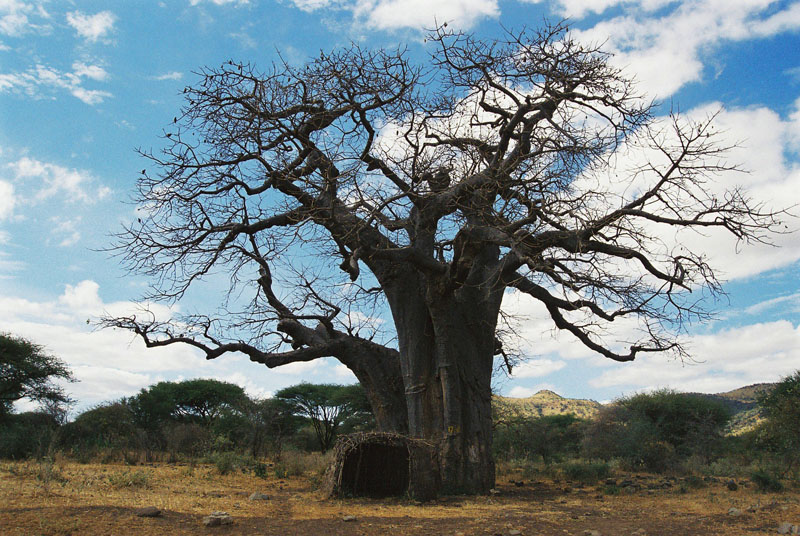

The film is directed by Seiichi Motohashi, a documentary filmmaker based in Japan, who journeyed to Touba Toul with the intent of finding a connection to nature amidst imposing civilization. We follow the lives of the local people as they follow the seasons, noticing the common priority of food over education, money, and social advancement. At the heart of the film is the baobab tree— the source of sustenance, spirituality, medicine, fuel, and identity for the villagers.

Visually, the film is comprised of extremely long takes of the landscape and village life. At a certain point, a villager’s winding description of the harvest of fruit cuts to a low-angle shot of a humongous baobab with six or seven figures floating upon its twisted limbs—it is stunning.

The musical score is simple and humorously hit-or-miss with its alternation from minor-key jazz pieces to more organic songs on the African hand-harp. However, layers of French dialogue and native dialect blend with the Japanese narration and rural ambient noise in a soothing and immersive melody. Furthermore, the minimalist editing flows well and enhances the quiet tone in every subtle way.

As I said, One Thousand Year Song of Baobab graciously avoids an activist’s urgency and unfolds naturally as documentation of a way of life. In a reflection of the villagers of Touba Toul, Seiichi Motohashi accepts the inevitability of modernization and turns his focus to appreciating the baobab (and the thousand years of village life it represents) while it is still standing. This beautifully-shot expression of passivity is sad yet honest, for this film is truly an artist’s way of preserving the past.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “One Thousand Year Song of Baobab (Motohashi, 2009): Japan,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 02.22.10 / 6pm

- Category:

- Documentary, Films, Santa Barbara Film Festival 2010

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]