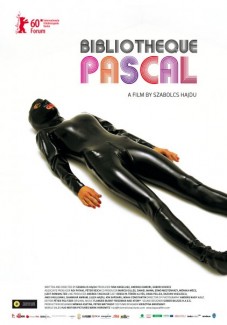

Bibliothéque Pascal (Szabolcs Hajdu, 2010): Germany, Hungary, UK, Romania

Reviewed by Richard Feilden. Viewed at Regal Cinemas, Los Angeles Film Festival.

Fantasy and surrealism can be used in many ways in film. Sometimes the audience is free to simply grab a hold of the crazy train and enjoy the madness, as is the case in Buñuel and Dali’s Un Chien Andalou, a film which actively resists closer examination. Alternatively, the strange can be a metaphor for tragedy, as in Pan’s Labyrinth, and is ripe for analysis. It can even be a mask for the terrible things that transpire in reality, as occurs in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Firmly embracing the Lynchian mode, Bibliothéque Pascal, directed by Szabolcs Hajdu sweeps you away with images both joyous and perverse, but something in the depths is always there to bring the horror crashing back down.

The film is bookended by an interview with child services. Mona (Orsolya Török-Illyés) is trying to regain custody of her daughter, whom she left with an aunt with rather unorthodox ideas about raising a youngster. She begins to recount a tale of gypsies, outlaws, kidnapping, dreams that leak into reality, white slavery, role-play prostitution and ghostly marching bands. If the story is true, then the world of fantasy is perhaps more terrible, if less tedious, than reality, and thus no escape. If a fabrication, then what horror can she be concealing?

Bibliothéque Pascal is concerned with human weakness. In a Q&A with the director, comments were made regarding the film’s rather grim view of men who range from despicable fathers, through homophobic thugs to brutal pimps and johns. While entirely fair, the women in the film fare little better in reality. Mothers who leave behind their children, and aunts who ply them with alcohol and put them to work on the stage, are only a little better, though desperation my drive them. Mona is certainly a tragic figure, but complex enough to be interesting. You’ll sympathize with her by the end of the film, but you’ll still question her actions. In a make-believe world, Hajdu has made sure that she is real.

Unlike Lynch, Hajdu does not wrap his film in layers of obfuscation and confusion. This clarity, while perhaps detracting a little from the film’s appeal to those who take pleasure from entwining themselves in the master’s analytic tangles, brings the characters to the forefront. If it is less intellectual than Lynch’s work, it has a greater ability to connect on an emotional level. He clarifies the ‘what happened’, leaving the audience to focus on the effects upon the characters. Thus the film gains accessibility, while sacrificing a little complexity. It’s a fair trade off.

The visuals in this film are the cherry on the cake. Once we enter the fantasy world of Mona’s imagination, the film immediately becomes more vibrant, if unpleasant, as though Amélie had stumbled into Gotham City. From train stations and beach huts to fairgrounds and brothels, everything that Mona encounters glows with the intensity of the hyper-real, merging real-world poverty and dark fantasy to astounding effect. Set design, particularly in a literary themed brothel, is spot on, with initially complex staging giving way to sparser sets as Mona’s numerous concerns are narrowed down to a primal desire for escape. The film slips effortlessly through a spectrum ranging from the slightly twisted to the truly absurd, culminating in the films bitter-sweet final scene. In this regard it holds its own with the best.

Bibliothéque Pascal comes highly recommended. Hajdu has woven a dark tale that challenges us in our understanding of its characters and world, woven into exquisite imagery. In another year it might easily have walked away with my ‘best of the festival’ award. It’s a wild ride with a hard landing, but one that I’m eager to take again.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Bibliothéque Pascal (Szabolcs Hajdu, 2010): Germany, Hungary, UK, Romania,” an entry on Student Film Reviews

- Published:

- 07.03.10 / 6pm

- Category:

- Films, Los Angeles Film Festival 2010

No comments

Jump to comment form | comments rss [?] | trackback uri [?]